‘The 940’ plays a very important role in the history of the Southwest Ring Road. It is the centre of ring road planning from the very beginning, and in many ways remains the key to an alignment on Tsuu T’ina lands. But what is the 940?

The 940 is a 940 acre parcel of land that makes up the north-east corner of the Tsuu T’ina reserve. It is bordered by the City of Calgary on two sides, 37th street SW and Lakeview to the east, Glenmore Trail and Glamorgan to the north, and the Elbow river and Weaselhead defines its south and west borders. Every official alignment of a major road in this area has the road cutting directly though the heart of this land.

History of the Land

The 940 was part of the Tsuu T’ina reserve granted in 1883. At this time it was the closest point to Calgary, sitting approximately 8km south-west of Fort Calgary.

Though set aside for the sole use of the Tsuu T’ina, external interest soon lead to offers to buy parts of the reserve, particularly the north-east corner. The first recorded request to subdivide and sell a portion of the land came in 1901, and hasn’t let up since.

Though set aside for the sole use of the Tsuu T’ina, external interest soon lead to offers to buy parts of the reserve, particularly the north-east corner. The first recorded request to subdivide and sell a portion of the land came in 1901, and hasn’t let up since.

The Tsuu T’ina chief at the time of the Signing of Treaty 7, Chief Bull’s Head (pictured below), was a staunch supporter of retaining the land for his people. He steadfastly refused to entertain the idea of selling any of the reserve. In 1904 he said:

We are of one mind not to sell or give up any of our Reserve. We don’t want to quarrel about it, we don’t want to sell. The Reserve is just big enough for ourselves, the whitemen are bothering us to give up our land. The Treaty was made. We will try not to be cross about it. I am just as friendly as ever, I don’t want to quarrel.

It wasn’t until after his death in 1911 that inroads were made by those seeking to open up the reserve for development.

Surrender

In 1913 the Tsuu T’ina agreed to surrender 1650 acres of land comprising the north part of the Weaselhead and the 940, which meant that the Tsuu T’ina gave up their rights to this land which was legally removed from the reserve. This was done on condition that the land be sold on the open market, and that a minimum price be obtained.

There were many parties interested in buying the land that the Nation surrendered, including the City of Calgary (for park land), the Canadian Military (for training grounds) and local businessmen (for commercial and residential development). In 1913, the land was surveyed and subdivided, as shown in the map below.

To complicate matters, 1913 marked a downturn of the economy, and with depressed development came depressed land prices. The land was withdrawn from sale because the Department of Indian Affairs believed that the land would not realise a fair price in the prevailing economic climate. They believed it was not in the best interest of the Nation to continue with the sale at that time.

While 593 acres of the surrendered land, the Weaselhead, was eventually sold to the City of Calgary in 1931, the outbreak of war in 1914 forever altered any plans for the area.

Military Use of the Land

The Canadian Military first used portions of the Tsuu T’ina reserve, particularly the 940, in 1910. After using it again in 1911, the Military gained leases on portions of the land from 1913 to 1952.

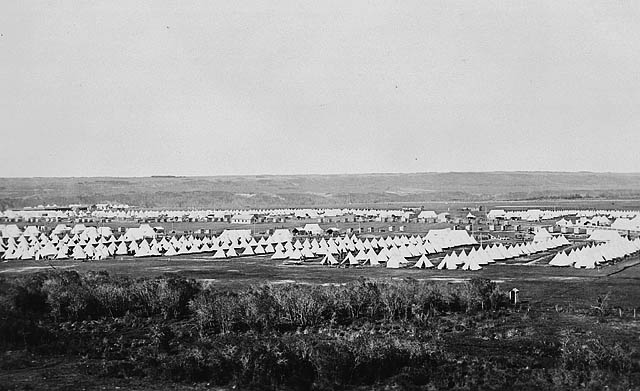

Following the withdrawl of the surrendered land for sale, and after the outbreak of the first world war, the military’s use of this land for training soldiers intensified, eventually becoming one of the largest Military bases in western Canada, training and housing up to 15,000 soldiers at one time. This area was eventually called the Harvey Barracks Camp (originally Sarcee Camp and Sarcee Barracks). The area is still marked by the history of the Sarcee Camp; the numbers on Signal Hill are the numbers of some of the regiments based there. Pictured below is the camp in 1915.

Once the land had been used so intensively by the Military, including artillery shelling, tank maneuvers and small-arms training, it was deemed by the Department of Indian Affairs to be unsuitable to use for anything other than military training. Any plans for sales for park land and development were shelved. Finally, in 1952, the Military purchased the remaining 940 acres of the surrendered lands, and was annexed into the City of Calgary in 1956. The annexation caused the city limits on the western edge of the city to move from 37th street SW to follow the 940’s southern boundaries along the Elbow river. This means that when the neighbouring community of Lakeview was constructed in the 1960s, it was not adjacent near the city limits.

Once the land had been used so intensively by the Military, including artillery shelling, tank maneuvers and small-arms training, it was deemed by the Department of Indian Affairs to be unsuitable to use for anything other than military training. Any plans for sales for park land and development were shelved. Finally, in 1952, the Military purchased the remaining 940 acres of the surrendered lands, and was annexed into the City of Calgary in 1956. The annexation caused the city limits on the western edge of the city to move from 37th street SW to follow the 940’s southern boundaries along the Elbow river. This means that when the neighbouring community of Lakeview was constructed in the 1960s, it was not adjacent near the city limits.

Today

After Tsuu T’ina offers to re-purchase the land were rebuffed by the Military, they sued to recover the land. In 1982, a legal action was launched over the 940, claiming that the sale in 1952 was improper, due to coersion. After a decade of talks, the land was returned in 1992 to the Tsuu T’ina in an out-of-court settlement, with the Military getting the option to lease portions of the land until 2050. The Military closed the Harvey Barracks in 1996, and in 2006, after 15 years of ordinance removal to return the land to its natural state, the 940 was finally returned. More than 90 years after the original surrender, the land was fully back in the hands of the Tsuu T’ina.

Road Plans and Beyond

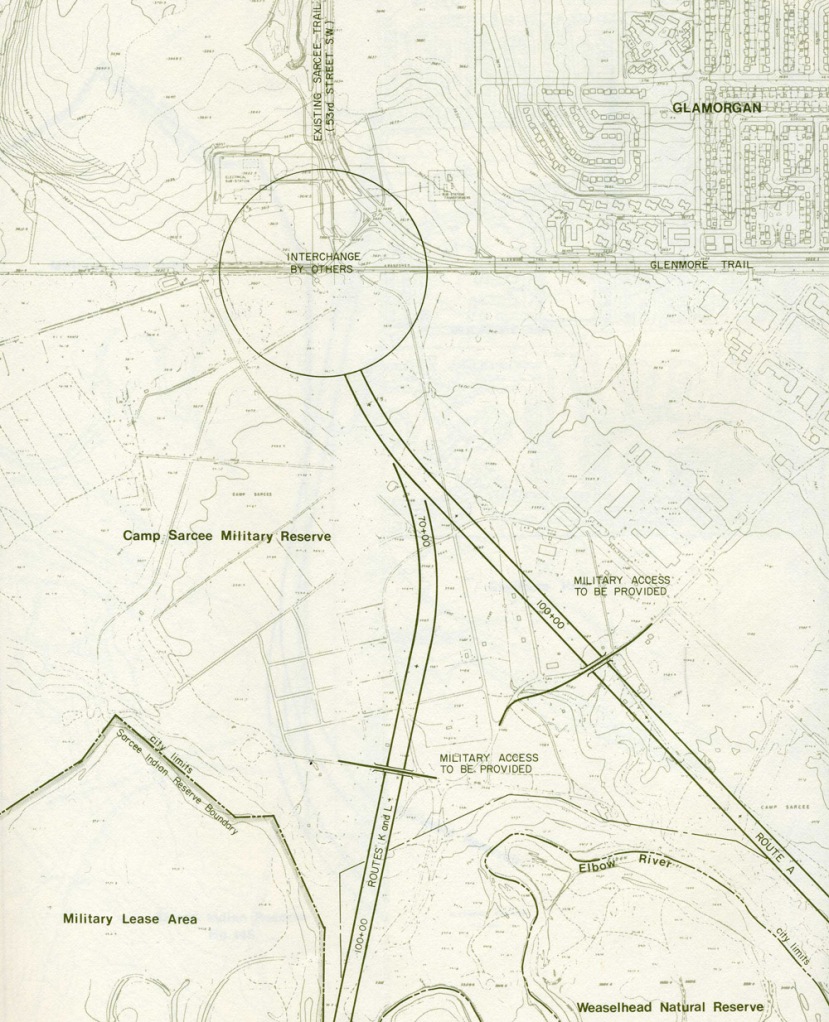

The 940 has been identified as the location of the northern section of the road in every official ring road plan ever produced, starting with the 1959 Calgary Metropolitan Area Transportation Study, where this road was first proposed. In these early studies, the road was planned to run directly south from Sarcee Trail, angling south-east through the Harvey Barracks and the Weaselhead, and finally connecting to the 37th street SW corridor at 90th avenue SW. These early alignments were contained within the city limits for the entire length, and the Military was consulted on the route, so as to minimise the impact of the road on the facilities at the Barracks. Below is an image from the 1977 Sarcee Trail Extension study, showing potential routes through the Harvey Barracks.

By the 1970s, the early routes that cut through the Weaselhead had lost favour, and a newer alternative that skirted the Weaselhead was endorsed by both Province and City (more on this in a future article). This route required Tsuu T’ina land south of the Elbow river, and the Province and City were committed to negotiating with the Tsuu T’ina for land.

Part of the appeal of a road on the reserve, from the Nation’s perspective, was the economic opportunities a road would bring. Before the 940 was returned, development opportunities were focused on reserve land south of the Elbow river, but after 1992, those plans shifted north to the 940. The casino that was built there in 2007 is only the first step of a much more ambitious development masterplan (more on this here), but that plan is reliant on the major road access that a Ring Road would provide.

Despite a long and complicated history, this parcel of land consistently finds itself at the centre of dispute, intrigue and political maneuvering. It continues to be a key component in plans for both the Province and the Tsuu T’ina, and that perhaps a common desire may prove to be the key in land negotiations; the possibility of both sides wanting a deal so that they can each develop portions of this land for their own benefit.

Looking for something else, I came across this fascinating piece of Canadian history. It made for very interesting reading for a retired history teacher. (The “something else” is information about a Sarcee Military Camp bar. It consists of the Union Jack, Sarcee Camp insignia and I presume the provincial flag. Nothing found.)

That’s interesting. I believe that the Military lease on that land had some alcohol prohibition, so I would be interested to know more. Glad you liked the article!