The Weaselhead Flats park is a 593.5 acre area of the Elbow River valley upstream of the Glenmore Reservoir in Southwest Calgary. The first recorded mention of the name ‘Weaselhead’ in relation to the Elbow river valley dates back to the 1890s, but where did the name originate? Why do we call this park, and the rest of the valley within the Tsuut’ina Nation reserve, ‘Weaselhead’?

There are a number of explanations for the origin of the Weaselhead name, and while some details may never fully be known, we can begin to learn the story of where the name came from, and how the area came to be known as the Weaselhead.

Conflicting Origin Stories

The City of Calgary acknowledges that the origin of the name of the Weaselhead Flats park is unclear, but points to the idea that the area was named after a Tsuut’ina man named Weaselhead. According to the City, the area is “…likely named after the Tsuu T’ina Chief Weaselhead who was in power at the time of European contact.”1

However, this isn’t the only origin story regarding the Weaselhead name; there is an alternative explanation known within the Tsuut’ina Nation which proposes just the opposite. In this version, Weaselhead was not Tsuut’ina, but a con-man from another Nation who was murdered along the banks of the Elbow river when his criminal ways caught up with him. According to this retelling, the name Weaselhead was then given to the area as a cautionary tale against adopting such a lifestyle.2

Clearly both cannot be true, and there is enough evidence that would suggest that perhaps neither is exactly right. Both stories say that Weaselhead was a man, but what do we know about this man, and how did he come to lend his name to this part of the Elbow River?

The Weasel Head crossing

In November of 1890, a spate of cattle thefts occurred at various ranches to the Southwest of Calgary, in the vicinity of the Tsuut’ina Nation reserve, then known as the Sarcee reserve. In one instance, a cow was reportedly killed along the Elbow river; a report notable because of how the location of the killing was described.

“About three weeks ago a cow… was killed by a Blackfoot Indian who had come across from the Blackfoot reserve and who left immediately after the killing for Macleod. The man is well known and is believed to be about the worst Indian on the reserve. This Blackfoot having slaughtered the cow in a secluded place on the bank of the Elbow, a little west of the Weasel Head crossing of that river, took what he wanted with him before heading south and notified the Sarcees to go for the remainder.”3

This brief mention marks the first recorded of the use of the Weaselhead name in relation to the Elbow River valley, and this crossing is where the name ‘Weaselhead’ would become well known and well used by both Calgarians and Tsuut’ina Nation citizens of the time.

In the late 1800s, the main road between the City of Calgary and the agricultural districts to the Southwest was a well travelled route known as the ‘Priddis Trail’ which bisected the Tsuut’ina Nation reserve. At the point where this trail crossed the Elbow within the reserve, the river widened and contained large gravel banks which provided an ideal place to ‘ford’ the river. This location came to be known as the Weasel Head crossing. (Click here for a detailed account of the Priddis Trail)

In 1900, the Territorial Government constructed a steel bridge across the Elbow river at location of the original crossing and was immediately named the ‘Weasel Head bridge’.4 This not only kept the name alive, but it helped to spread it out across the valley. In 1905 the Priddis Trail was moved downstream, and the Weasel Head Bridge was also moved.

Embraced by Calgarians

With the original crossing and the new bridge, both named ‘Weasel Head’, separated by about a mile, the entire valley between these two points began to be called by that name. The new road and bridge meant that the area was easy to access, and after the turn of the century it became known for its beautiful scenery and was increasingly used by campers, hunters and day-trippers.5

In the late 1920s the City of Calgary was planning to dam the Elbow River downstream of the Weasel Head bridge in order to flood the valley and create a reservoir of drinking water for City residents. The City recognized that part of the new Glenmore Reservoir would encroach into the Tsuut’ina Nation reserve, and so it set out to purchase the lands required for the project.

In 1931 Tsuut’ina representatives including Chief Joe Big Plume met with the City to discuss the sale of a part of the reserve for the Glenmore Reservoir project; land that comprised a significant portion of the Elbow River valley.6 The purchase was negotiated on behalf of the City by solicitor L.W. Brockington, who had previously been given an honorary name ‘Chief Yellow Coming Over the Hill’ by the Tsuut’ina Nation.

The Nation expressed concern over the loss of the Weasel Head name as a result of the reservoir. It was understood by both the City and the Nation that when the reservoir was to be created, this portion of the Elbow River valley would be flooded, and with the land ‘gone’, the Weasel Head name would disappear. A request was made of Brockington; if he would be willing to forgo his original honorary Tsuut’ina name, the Nation would bestow upon him the title of ‘Chief Weasel Head’ as a way of ensuring the name would live on.7 Brockington agreed to this request and the deal was finalized; Calgary now owned much of the Weaselhead area.

The land that was acquired by the City included the Weasel Head Bridge and was accompanied by Brockington’s new honorary title; and so despite the fact that much of what is now called the Weaselhead is not particularly close to the site of the original Weasel Head crossing, the name firmly attached itself to those lands. The Weaselhead name continues to apply not only the former reserve land purchased by the City (which, despite initial concerns, remains largely un-flooded), but also to the Elbow River valley upstream of the park within the Tsuut’ina Nation reserve.

During the course of negotiations for the Weaselhead lands, Nation representatives including Pat Grasshopper, Pretty Young Man and Running In The Middle recounted the history of the area and the “legends which surrounded the original camp grounds of the Sarcees.” This history included that a man named ‘Weazel Head’ was “…the chief of the tribe who use to pitch his teepee on the Weaselhead flats more than fifty years ago.”8 In recounting this history, the Nation gave Calgarians an early glimpse into the origin of this respected name.

Weazel Head the man

In 1887, British Member of Parliament William Sproston Caine embarked on a journey that would take him around the world. The Canadian leg of the journey would see Caine and his eldest daughter Hannah travel by rail from Montreal to Vancouver, and on Wednesday September 14, they stopped in the growing frontier town of Calgary. After touring several local cattle ranches, Caine and his daughter rode the seven or so miles to the Tsuut’ina Nation reserve with Department of Indian Affairs representative A. R. Springett.9

At that time of year, many Tsuut’ina citizens were camped near the Old Agency area of the reserve by Fish Creek, and were preparing to stay for the winter in small log cabins. The names of the owners of the assembled tipis were translated for Caine and his daughter, and among the 30 names mentioned was that of ‘Weazel Head’; one of the ‘braves’ of the Sarcee according to Springett.10

This encounter by Caine was not, however, the first time that a man named Weazel Head would enter the public record; that occurred just a few years earlier, in 1880.

Three years after the signing of Treaty 7, before the Nation settled onto the current reserve at Fish Creek, Weazel Head gathered at the original Tsuut’ina Nation reserve near Blackfoot Crossing with his two wives, three sons and three daughters.11 The family, the second largest of Little Drum’s band within the Nation, were each paid $5 as stipulated by the Treaty. The agents responsible for distributing the payments noted Weazel Head’s first appearance in their records, remarking that his name “cannot be traced”.12 Indeed this appears to be the first time that his name is recorded by any agency or Government.

Following the rejection of the original reserve near Blackfoot Crossing by the Nation, the Tsuut’ina people came in 1881 to what is now the current reserve, located southwest of Fort Calgary. Weazel Head and his family were a part of that migration, and they too settled on the new land. Around that time, Little Drum had died,13 and so Weazel Head transferred to Big Plume’s band for the following two years. Following the death of one of his wives, Weazel Head’s family transferred again, this time to Big Wolf’s band around 1883,14 where they were to remain.

In each of his transfers to new bands, Weazel Head was accompanied by a man called Running In The Middle; a bachelor in 1880 who would later marry. It seems likely that Running In The Middle was a friend or family, and years later he would tell the history of Weazel Head at the occasion of the Glenmore Reservoir land sale from first-hand experience.

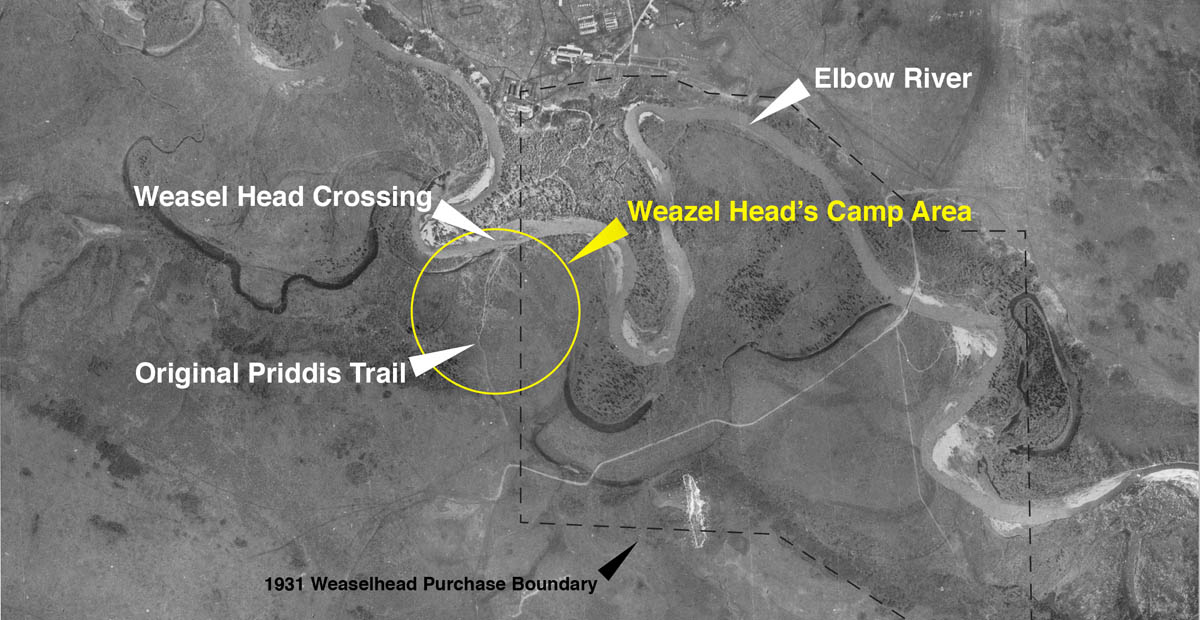

Tsuut’ina Elder Bruce Starlight recounts that Weazel Head made his camp at the foot of the hills on the south side of the Elbow river valley, “on one side or the other of the old main road”.15 Based on this description and the location of the original Weasel Head crossing location, we can identify the vicinity of where Weazel Head made his camp, at the west edge of what is now Calgary’s Weaselhead Flats park.16

In 1886, the Department of Indian Affairs had begun a practice of listing every individual who had sown or harvested a crop on a First Nation reserve, including the Tsuut’ina reserve. That year, Weazel Head was included in these agricultural records, having nearly 2 acres of land under cultivation.17

Weazel Head again appears in the 1887 records for agricultural cultivation on the Tsuut’ina Nation reserve,18 although the following year would be different. In 1888, despite sowing an acre of potatoes, Weazel Head is recorded as having harvested no produce at all. That season, every other Nation member who planted a crop, apart from one, harvested at least some produce, making Weazel Head’s lack of harvest notable.19

The next year, in 1889, the Government did not list Weazel Head in their agricultural records, and in Treaty pay sheets his absence was noted by a simple remark beside the entry for his family; “1 Man Died”.20

The Death of Weazel Head

Weazel Head died on April 4 of 1888.21 The death of both of his Wives and two of his daughters throughout the 1880s, along with his sons having grown up and left the group, meant that Weazel Head’s family camp was dwindling. When his last daughter married a man named Wolf around 1892,22 the Weazel Head family was removed from official records. Only a blank space, denoting the now-dispersed Sarcee family No. 118, remained on the Treaty pay sheets.23

In 1890 another British traveller, Alexander A. Boddy, made a similar journey throughout Canada to the one that William Caine had undertaken three years before. And like Caine before him, Boddy would also come to hear the name ‘Weazel Head’.

Boddy arrived in Calgary in June of 1890, and soon went to visit the Tsuut’ina Nation reserve. There he met the Anglican Minister Harry William Gibbon Stocken, who ministered to the Tsuut’ina. Together they toured portions of the reserve, and visited Tsuut’ina burial grounds south of the Indian Agency across Fish Creek. From there, they rode to the edge of the reserve, where they found the unique interment site of a man named Many Horses.

Many Horses was noted to be a ‘revered’ leader of the Tsuut’ina, and was “chief of the Sarcees when the white man first appeared in the neighbourhood”,24 according to Stocken. The grave site of Many Horses was different to the burials near Fish Creek, where the deceased were wrapped in blankets and placed in the limbs of trees to be reclaimed by nature. Many Horses’ resting place, by contrast, was “a wooden erection on the top of a hill”, adorned by a pole flying a makeshift flag.25

Looking through the gaps in the wood, Boddy could make out not only the body of Many Horses, but also that of another within a wooden ‘annexe’ attached to the main structure. Inside of this annexe was the body of “Weasel Head”,26 who Stocken also identified as a ‘chief’. It’s not clear if the unique way in which Weazel Head was buried offers any indication as to his status or position within the Tsuut’ina community, but it does appear noteworthy.27

Although Weazel Head had died in the spring of 1888, his name would not be forgotten.28

A Name That Lives On

Much has changed in the last 140 years in the Elbow River valley, including the flooding of the reservoir, extensive military use, the creation of a park and the transfer of much of the land out of the Tsuut’ina Nation reserve. And perhaps the largest change is taking place now.

In the 1930s, it was feared that the flooding of the valley would erase the land that bore Weazel Head’s name, and with it, the name itself. Nearly 90 years later that erasure of the land would come to pass, as the Southwest Calgary Ring Road is being constructed directly through Weazel Head’s old camp and river crossing. With the relocation of the Elbow river and the construction of embankments over the site of the old Weasel Head crossing, little is recognizable of the old valley.

Despite the loss of this land, the name ‘Weazel Head’ has spread much further afield since the man first set up camp along the Elbow river in the 1880s, and his will not be soon forgotten.

I want to express my gratitude and thanks to Bruce Starlight for taking the time to speak to me about the history of the Weaselhead. His knowledge and wisdom were invaluable in understanding this history. Any mistakes I may have made in recounting his information are mine alone. Thank you to Emil Starlight for help in making connections, both personal and linguistic. Thanks also to Rick Boden at Work Above aerial photography, workabove.com.

References:

1 ‘Weaselhead Flats’ City of Calgary website. Retrieved May 1, 2019. https://www.calgary.ca/CSPS/Parks/Pages/Locations/SW-parks/Weaselhead-Flats.aspx

2 – See for instance ‘Tsuut’ina Nation Series – Part 2’ Hal Eagletail, Lakeview Community Association. Retrieved May 1 2019. https://www.lakeviewcommunity.org/committee-reports/relations/part2

3 – ‘Killing and Stealing Cattle’ December 3, 1890. Calgary Daily Herald.

The similarity of this account to the alternative Weaselhead origin story that is told by some Tsuut’ina Nation citizens is striking; both features a non-Tsuut’ina indigenous man of low-repute temporarily visiting the Tsuut’ina Nation reserve, theft and other criminal activity, and a killing on the shores of the Elbow river at Weasel Head crossing.

4 – Annual Report. Department of Pubic Works of the North-West Territories. 1900. Peel Prairie Archives Peel 9536.14

5 – See for instance: “The Sarcee Reserve Worth Visiting” Calgary Daily Herald. July 24 1903, and “Pioneer Work of Charting Auto Roads Southern Alberta, begun by Calgary Auto Club in 1911, Has Been Help to Motorists” Calgary Daily Herald. July 17, 1915. and “Polo and Hunt Club Holds a Paper Chase” Calgary Daily Herald, July 17, 1924.

6 – “Unique Parley at Dam Site Purchase” May 5, 1931. Calgary Herald.

7 – “Calgary City Solicitor Now Known as ‘Chief Weasel Head” May 5, 1931. Edmonton Journal.

8 – “Unique Parley at Dam Site Purchase” May 5, 1931. Calgary Herald.

Fifty years prior to the Glenmore Reservoir negotiations was 1881, the year that the Nation first moved onto the land that would eventually become the Tsuut’ina Nation reserve. Significantly, Running In The Middle would have personally known Weazel Head, as both belonged to the same small bands within the Nation throughout the 1880s (15b – 1887)

9 – A Trip Round the World, W. S. Caine M.P. George Rutledge and Sons. 1888.

10 – Ibid.

11 – Indian Annuities – Treaties 4, 6 & 7. 1880. Public Archives Canada. Glenbow Archive.

12 – Ibid.

13 – Indian Annuities – Treaties 4, 6 & 7. 1881. Public Archives Canada. Glenbow Archive.

14 – Indian Annuities – Treaties 4, 6 & 7. 1883. Public Archives Canada. Glenbow Archive.

15 – Personal conversation with Bruce Starlight. April 10 2019.

16 – Interestingly the Southwest Calgary Ring Road now crosses the Elbow River in the same location as the original Weasel Head crossing.

17 – “Return showing Crops sown and harvested by Individual Indians in Sarcee Agency, Season of 1886” Dominion of Canada. Annual Report of the Department of Indian Affairs for the year ended 31st December, 1886.

18 – “Return showing Crops sown and harvested by Individual Indians in Sarcee Agency, Season of 1887” Dominion of Canada. Annual Report of the Department of Indian Affairs for the year ended 31st December, 1887.

19 – “Return showing Crops sown and harvested by Individual Indians in Sarcee Agency, Season of 1888” Dominion of Canada. Annual Report of the Department of Indian Affairs for the year ended 31st December, 1888.

20 – Indian Annuities – Treaties 4, 6 & 7. 1889. Public Archives Canada. Glenbow Archive.

21 – Register of Indian’s Death, 1888. Sarcee Reserve. Glenbow Archive, and Sarcee Deaths list, Tsuut’ina Nation archive.

22 – Indian Annuities – Treaties 4, 6 & 7. 1892. Public Archives Canada. Glenbow Archive.

23 – Indian Annuities – Treaties 4, 6 & 7. 1893. Public Archives Canada. Glenbow Archive.

24 – By Ocean, Prairie and Peak, Alexander A. Boddy, F.R.G.S. Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. 1896.

It is interesting to note the wording in Boddy’s account of who Many Horses was, especially in relation to modern explanations of the Weaselhead name. This 1890 account states that Many Horses was “…Chief of the Sarcees when the white man first appeared in the neighbourhood”, which is remarkably similar to the City’s statement that Weazel Head was likely “…the Tsuu T’ina Chief… who was in power at the time of European contact.”. This similarity raises the possibility that Many Horses and Weazel Head have been confused with each other in later retellings of this specific account.

25 – Ibid.

26 – Ibid.

27 – A recurring assertion about Weazel Head is that he was a Chief of the Tsuut’ina Nation, but despite his unusual burial, there exists no evidence or contemporary recollection to suggest that this was the case. Between 1880 and 1888 Weazel Head received an annual Treaty payment of $5, rather than the $10 afforded to Minor Chiefs or the $15 reserved for Head Chiefs of Treaty 7 Nations. Weazel Head also belonged to three bands led by three Minor Chiefs in the 1880s, Little Drum, Big Plume and Big Wolf. Records do not show Weazel Head as leading a band of his own.

28 – Bruce Starlight recalls that Margaret Dixon Runner, a Tsuut’ina Elder who passed away in 2015, told him about meeting a man who was called Weaselhead. (Personal conversation with Bruce Starlight. April 10 2019.) She described him as a short, stocky man, who was introduced to her as being ‘family’, however as Margaret was born in the 1930s, this could not have been the original Weazel Head that the Elbow River valley is named after. Runner may have met a man called Dick Night, who was reportedly also known by the name ‘Weasel Head’ (Glenbow Archives NA-667-479). The historical record shows that Dick Night emerges within the Nation’s records as an unmarried man about three years following the death of Weazel Head, but there is no indication as to the relationship, if any, between the two men.

Excellent scholarship! I grew up in Lakeview and spent many pleasant hours riding my bike or cross-country skiing through the Weaselhead park area. I’ve always been fascinated by this beautiful area.

Some more information on Leonard Brockington, including his role as Chief Yellow Head Coming Over the Hill is here

Click to access Leonard-Brockington_A_Life.pdf

Very interesting, thank you for sharing that.