The October 2013 ring road agreement between the Province of Alberta and the Tsuut’ina Nation has recently been heralded by the Province and the media as a historic agreement between these two parties. While the scale, compensation and long-term impacts of this deal are indeed unique, representing the largest ever land purchase from the Tsuut’ina reserve and the potential opening of the reserve for unprecedented development, it is not the first time a road corridor has been acquired by the Province through the reserve. The ring road agreement actually represents the seventh time that a Provincial road corridor has been secured through Tsuut’ina lands.

1. Priddis Trail, 1900

1. Priddis Trail, 1900

2. 37th Street SW, 1910

3. Priddis Trail Diversion, 1916

4. Highway 22/Bragg Creek Road, 1922

5. Balsam Avenue Bridge Approach, 1934

6. Highway 22 Widening, 1955

7. Southwest Calgary Ring Road, 2013

1: Priddis Trail, 1900

The Priddis Trail was the first Provincial/Territorial road to be formally established through the Tsuut’ina (then Sarcee) reserve when an order of the Privy Council of Canada accepted a land surrender by the Nation on February 5 1900. The original request for the land having been made by the Government of the Northwest Territories in 1899, only 16 years after the establishment of the reserve in 1883.

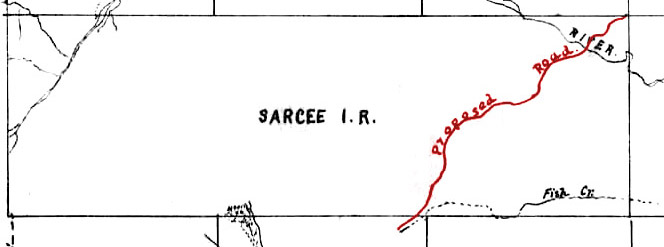

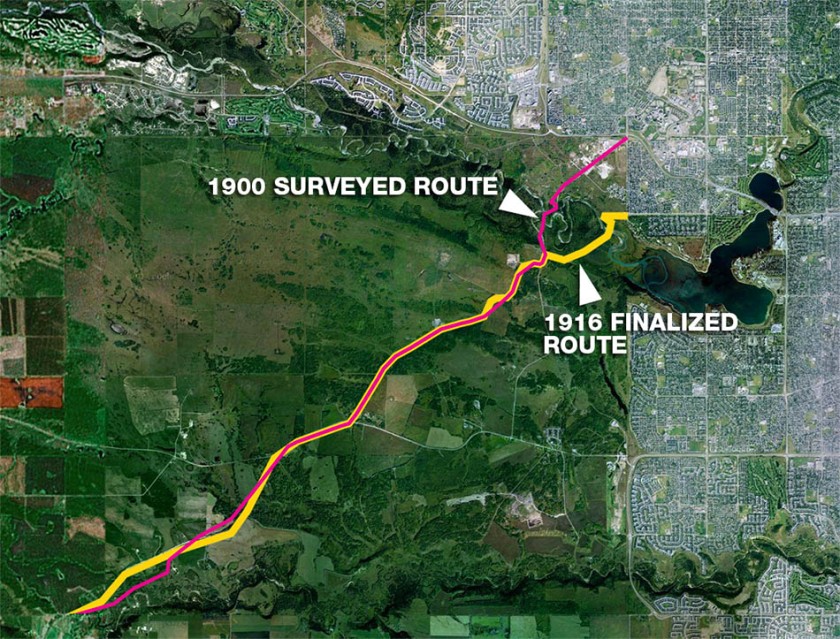

The Tsuut’ina agreed to a surrender of the lands based on a very basic speculative sketch drawn in the summer of 1899 (above). This sketch formed part of the agreement, and was based on the route of an old First Nations trail that had been in use since before the establishment of the reserve and the signing of Treaty 7. The corridor for the road was originally surveyed from the northeast corner of the reserve, at what is now the intersection of Glenmore Trail and 37th street SW, in a southwesterly direction to the reserve’s southern border, and new surveys in 1903, 1904, 1905, 1907 and finally 1916 would alter the route of the road from this original path. Though the path for the road changed and new lands were added and removed from the corridor (most notably in the Elbow valley through the Weaselhead), no further permission was sought or obtained to make these often significant adjustments.

Questions about the ownership of the road arose throughout the existence of the road, and the surrender and land transfer was later challenged by the Nation. The Tsuut’ina have argued in legal proceedings that the original surrender was not intended to dispose of the land; it was meant only to provide an easement to allow the government to build a road through their land, while the land was to have remained the property of the Tsuut’ina. Indeed the surrender agreement provided no compensation for the land required for the road and the Nation received no money or land in exchange for this surrender. In addition, the Province failed to transfer the land title at the time of the agreement, and only legally gained title to the land as a result of the passage of the 1930 Constitution Act, which transferred control of ‘undedicated’ crown lands from the Federal Government to the Province of Alberta.

In the 1980s, decades after the road had effectively been abandoned by the Province, the Nation was successful in efforts to have the majority of the Priddis Trail lands returned to the reserve. Of the remaining lands not returned, the status of the 10.23 acre portion located in the Weaselhead park was resolved in 2013 as part of the Glenmore Land Claims, leaving only a 1.2 acre portion whose status is still potentially unresolved.

The route that was finalized in 1916 contained 76.5 acres of land, of which only 11.43 acres remain under the ownership of the City of Calgary or the Province of Alberta.

For more about the Priddis Trail, click here.

2: 37th street SW over Fish Creek, 1910

In 1910 the Province again sought to secure the surrender of a strip of land within the Tsuut’ina reserve in order to accommodate a road south of Calgary, this time for a diversion of 37th street SW.

The road, located directly adjacent to the eastern border of the Tsuut’ina reserve, was being extended to serve rural areas south of the City, and this necessitated a crossing of Fish Creek. A diversion from the original road allowance was required in order to avoid the steep slopes of the Fish Creek valley that was found along the direct route of the original corridor. In order to provide reasonable grades, the road would have to head either east or west, descend gradually into the valley where it would cross the creek, and then head back onto the original road allowance. While the Province eventually built a bridge over Fish Creek to the east of the original 37th street SW road allowance (shown in orange below), plans were also put in motion for the diversion to be built to the west, within the Tsuut’ina reserve (shown in blue).

In June of 1910 the Nation agreed to a surrender of a 66-foot wide corridor comprising 3 acres of the reserve, and by August of that year the Governor General approved the land transfer. It is unclear if any compensation was offered in return for the land.

Despite the approval, this road allowance went unused when a more easterly crossing of Fish Creek was built. Though the City of Calgary places a date of 1907 for the construction of the 37th street SW bridge across Fish Creek, this may not be the case; in addition to Provincial records failing to note a steel bridge at this location in a complete listing of steel bridges of Alberta in 1909, it seems unlikely that the Province would go to the trouble to secure a corridor through the reserve if a bridge had already been constructed over Fish Creek just east of the reserve. Unused and unneeded by the Province, the current status of this land is also unclear. Federal records do not show if this land was ever formally transferred to the Province, and if it was, if it was ever returned to the Nation. Indeed, a formal survey appears not to have been undertaken or registered for this right of way, and reference to this road does not appear on later general surveys.

103 year later, however, it appears that the province will take possession of at least a portion of this corridor. The 2013 Southwest Calgary Ring Road deal includes about half of this land as part of the agreed transfer of land to the Province.

For more about 37th Street SW at Fish Creek, click here.

3: Priddis Trail Diversion, 1916

In 1916, the Province was looking to straighten portions of the Priddis Trail, and had undertaken a new survey on the road to formalize all of the previous alterations into a single, finalized route. At the same time, a survey of a new road which connected the Priddis Trail to the southern border of the reserve was also completed by the Province.

The surrender of the land for this road, agreed to by the Nation in January of 1916 and accepted by the Federal Government in 1920, specifically contained no compensation for the Nation. In addition, like the Priddis Trail surrender before it, the intentions of the Nation regarding the surrender is subject to interpretation. The surrender stated that the Nation ‘agree(s) to grant permission to the Alberta Government to allow a road to be built… as a high way’, making no specific reference to a sale or transfer of land and which might also be interpreted as consenting to an easement rather than a land sale.

Along with the Priddis Trail, the entire 5.96 acres of land for this road was returned to the Tsuut’ina in the 1980s.

4: Highway 22/Bragg Creek Road, 1922

5: Balsam Avenue Bridge Approach, 1934

In 1921, the Province of Alberta surveyed an old trail (Shown in the map below from 1897) that crossed the northwest corner of the Tsuut’ina reserve in order to formalize this route into a provincial road. The survey plotted a 66-foot-wide strip of land along the route totalled 43.63 acres and would form the westerly portion of the Calgary to Bragg Creek road (also known as the Bragg Creek Road), and today is part of Highway 22.

Seeking to purchase the land for the road in 1922, the Province was presented with a valuation of $20 per acre by the Indian Agent that represented the Tsuut’ina. Though the Province undertook clearance and grading of the Bragg Creek Road that year, the transaction for the land through the reserve was not completed; the road was built on land not owned by the Province, and would remain that way for over a decade.

In 1932 the Elbow River recorded its largest ever flood event, which resulted in the destruction of the old wood bridge serving Bragg Creek. When a new steel bridge was being built as a replacement for the lost structure, the location of the crossing was moved several hundred feet downstream which necessitated the construction of a new bridge approach road. The new location placed the bridge nearer to the border of the Tsuut’ina reserve, and the approach road, now known as Balsam Avenue, was planned to intersect with the Bragg Creek Road slightly inside of the reserve (see map below). This plan meant that the Province would have to purchase a small strip of land from the Tsuut’ina in order to accommodate these plans.

In 1934, while seeking the required land for the new bridge approach, the Province apparently noticed that the original purchase of the land for the Bragg Creek Road through the reserve had not been completed. While inquiring about the price and purchase of the new approach lands, the Province also sought confirmation that the original $20 per acre price quoted 12 years earlier would be satisfactory to the Indian Agent, not only for the new approach land, but also for the completion of the original Bragg Creek Road purchase. This price was approved, and total of $881.40 was paid for both strips of land.

The Province appears to have dealt exclusively with the Indian Agents representing the Tsuut’ina at the time, and not with the Nation itself; the land was expropriated from the Nation for road purposes under section 48 of the Indian Act in effect at the time. No approval or surrender by Nation members is on record when the Privy Council approved the land transfer to the Province in 1934.

For more about Highway 22, click here.

6: Highway 22 widening and straightening, 1955

In the mid 1950s the Province undertook an upgrade of the Bragg Creek Road, now known as Highway 22, in order to widen and straighten it. The existing corridor through the Tsuut’ina reserve was 66-feet wide, and contained numerous jogs and corners. In order to accommodate the planned upgrades, the Province began discussions to acquire the land for the new road, as well as abandoning certain lands that would no longer be needed. In March of 1955 the Nation passed a Band Council Resolution agreeing to the sale and a price for the new lands needed for the road.

(Illustrated road width not to scale)

Rather than abandoning portions of the old road and purchasing new lands in a piece-by-piece fashion, the decision was made to instead return the entire existing road allowance to the Tsuut’ina, and then purchase the new corridor outright. A survey of the new corridor, including the original Balsam Avenue bridge approach, was completed in 1956, and by December the existing lands were returned to the Federal Government and reintegrated into the reserve. Earlier that summer the Province had began the work of widening and straightening the road according to the new survey, and was finished before the new lands had been officially transferred to the Province.

The following year the Federal Government transferred the new 99-foot-wide corridor to the Province and the additional lands cost the Province $2124, or about $103.61 per acre. The total area contained in the corridor for Highway 22 increased to 64.57 acres, and ended up costing the Province a total of $3005.40. This corridor remains unchanged to this day.

7: The Southwest Calgary Ring Road, 2013

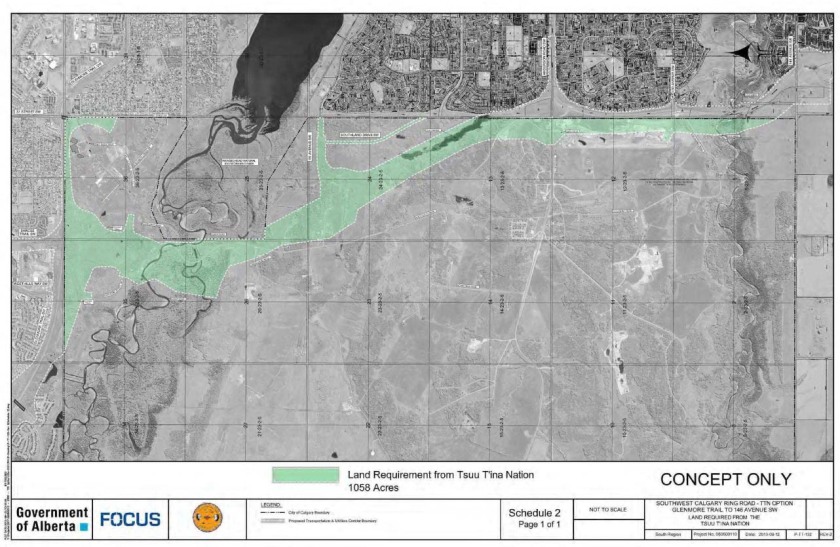

In October of 2013, Tsuut’ina Nation members voted to accept a deal negotiated between the Nation and the Province of Alberta for land required for the Southwest Calgary Ring Road. The deal, a direct culmination of negotiations begun in 2003 and indirectly from discussions begun in the 1970s, represents the single largest purchase of land from the Tsuut’ina in the 130 year history of their reserve.

The Province acquired 1058 acres of land required for the road and utility portion of the Calgary Ring Road project, while the Tsuut’ina will receive $275,000,000 as well as 5018.1 acres of land to be added to the reserve. In addition, a further $65,643,900 is provided to the Nation to rebuild or relocate housing and businesses located in the path of the ring road, and the Nation will be able to purchase and additional 320 acres at their own expense to be added to the reserve. Finally, interchanges are to be built that connect to the reserve, so that Nation lands can have access the road in order to facilitate commercial development there.

Though Nation members have agreed to the sale and transfer of the land for the ring road, the agreement has not officially been signed; this is due to occur sometime this month. Once this is completed, the Federal Government will be called upon to complete the land transfers involved, and to set aside the Tsuut’ina’s new lands as a reserve for the benefit of the Nation. While this process can take months or even years to complete, it is only once this has taken place that construction of the Southwest Calgary Ring Road can begin.

For more about the 2013 Southwest Calgary Ring Road deal, click here.

The Last Corridor?

Despite the historic nature of the newest road agreement between the Province and the Tsuut’ina, it represents only the latest in a series of right-of-way acquisitions of reserve land for road purposes, though It may also be the last. The 2013 agreement essentially allows for the construction of two roads through the recently agreed road corridor; the current Stoney Trail and a future ‘outer ring road’. The plan was structured in this way because it was made clear by the Tsuut’ina that a second road corridor to accommodate a future outer ring road would not be forthcoming, and any crossing of the reserve would have to be done in the newly agreed-upon corridor only. Indeed earlier plans for another road, Highway 922, faced similar concerns regarding its proposed crossing through the middle of the reserve, and was eventually scrapped altogether.

An Evolution of Building Roads and Building Bridges

There is a marked contrast in the way road deals have changed in the 113 years between the first agreement for a road through the Tsuut’ina reserve and the latest ring road deal. While early surrenders were obtained without any direct compensation to the Nation, and mid-century deals provided modest payment, the 2013 deal represents a shift towards a more significant compensation package for the Nation, and for the first time included new land in exchange for the land relinquished by the Tsuut’ina. It can also be said that for the first time the Nation were an equal party at the negotiating table, agreeing to a deal that would benefit the Nation as much as it did the Province, which has not always been the case.

The documentation around the original surrenders have also evolved over time. The first road surrender, for the Priddis Trail, contained only 286 words, much of it hand written, and relied on a sketch to detail the proposed corridor. The 2013 agreement by contrast runs 81 pages and contains eight pages of technical drawings of the proposed road, along with two land transfer maps. Given the legal issues that have surrounded past land sales and surrenders, it is unsurprising that all parties involved in the new agreement are seeking greater clarity in what the agreement entails.

Road deals between the Province and the Nation have evolved over time, much like the overall relationship between the Province and the Nation. Unlike many of the previous deals, the new ring road agreement has been lauded by both sides as providing benefits to all involved, as well as providing literal and metaphorical connections between the communities involved.