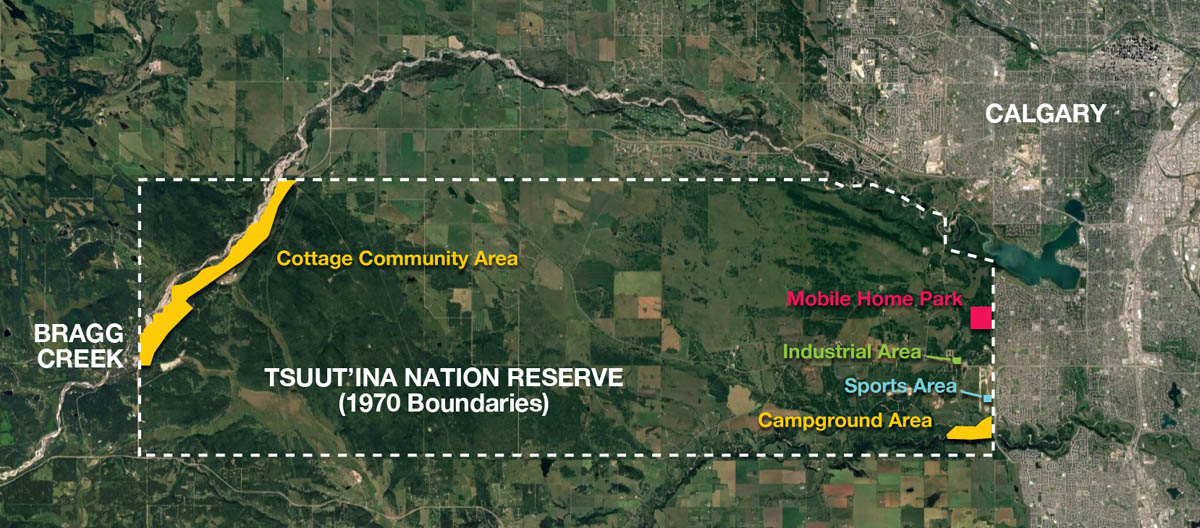

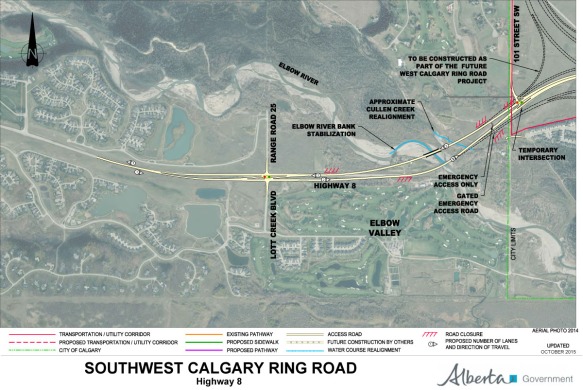

One day you may find yourself taking a walk in Calgary’s North Glenmore Park, along a pathway that connects a small parking lot to an expansive overlook of the Elbow river valley. Along that walk you would be forgiven for thinking that you were still within Calgary city limits, and that the land you were crossing was owned by the City. It’s an easy mistake to make, and it is one that has been made in one form or another for over 100 years. This unassuming land, measuring only half a hectare or 1.25 acres in area, was quietly taken from the Tsuut’ina Nation over a century ago, but continues to be claimed by the City.

A close look at the history of this ‘disputed parcel’ shows an unusually complex past, and reveals the improper dealings that led to the land being removed from the Tsuut’ina Nation reserve. By exploring this story we can see the understandable, yet shaky, assumptions on which Calgary claims of ownership this land, and perhaps recognize that it may be time for it to be returned.

To understand how the City of Calgary came to ‘own’ this land, we first have to look at the history of this part of the world, and the surprising use of this disputed parcel as part of an old Provincial highway.

(I recently had a short interview with the CBC regarding the disputed parcel, it can be found here.)

Back to the Beginning

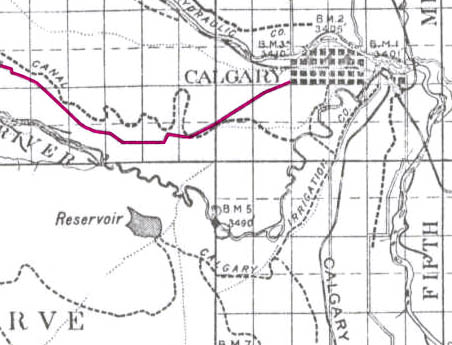

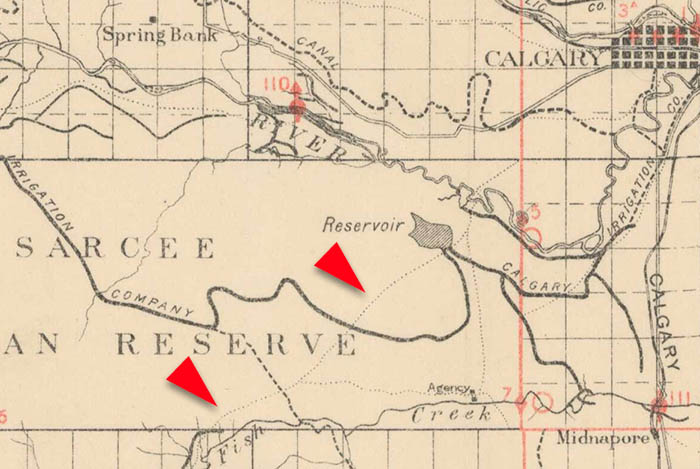

In the early years of European settlement of western Canada, homesteaders living in the Priddis and Millarville area, in what was then the North West Territories of Canada, relied on an old trail to access Calgary. This trail headed southwest from the city and crossed the Tsuut’ina Nation (Sarcee) reserve, and was reportedly in use since before the reserve was established in 1883.01 This dirt trail was not formally constructed or maintained, and suffered from chronically poor drainage; in wet years it often proved impassible for significant periods of time. As local ranchers and homesteaders relied on this route to access Calgary and bring their produce to market, the old trail was a vital link in a growing ranching district. (Read more on the history of the Priddis Trail)

The unreliability of the road was a chronic problem, and the Government of the Northwest Territories was pressed by local politicians and residents to improve the road.02 As the trail was an organically-created path that was located on Federal land reserved for the Tsuut’ina Nation, the Territorial Government wanted to acquire the right-of-way for the road before it expended any public money on improving and maintaining the road as a public highway.

Initially the matter was intended to be pursued as an expropriation of the land under the terms of Treaty 7 and the Indian Act, but the Territorial Government decided that it would be easier to instead secure a transfer agreement rather than acting unilaterally in order to take possession of the land.03

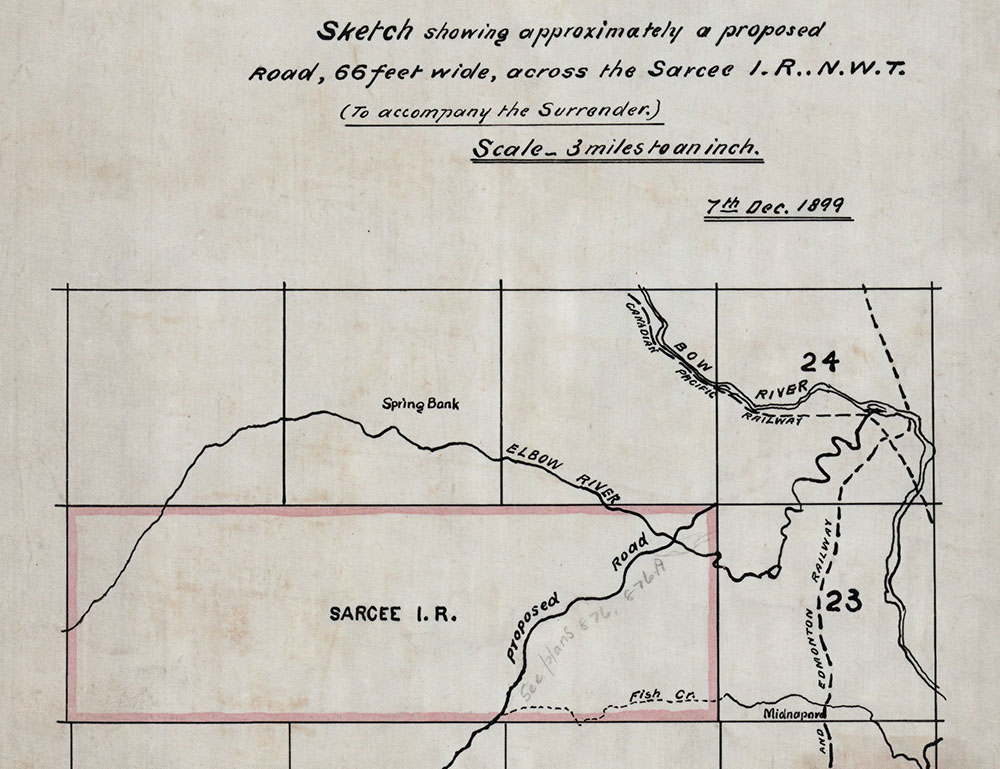

The Government of the Northwest Territories instructed its Department of Public Works to survey the road, and reached out to the Department of Indian Affairs in the spring of 1899 to seek consent for “…the transfer of the area therein contained after the survey is completed so that it may be declared a public highway.”04 That request was forwarded to the local Indian Agent to see if the Tsuut’ina Nation had any objection to the opening of the road. After discussions with Tsuut’ina Chief Bullhead, the matter was put to a meeting of the male citizens of the Nation. Informal permission was granted not only for the survey to take place, but also for the Government to improve and open the old trail as a public highway.05

“The Chief informed me the trail marked in the plan was in use by the Indians before the treaty was made with them.”

Indian Agent, Sarcee Agency. May 16, 1899.1

Securing a Surrender

In Canada, First Nation reserve land is owned by the Federal Government and reserved for a specific First Nation. Under the Indian Act, this land cannot be sold or transferred (outside of an expropriation) without the interested Nation first ‘surrendering’ their interests in that Federal land. Once surrendered, the land remains in the hands of the Federal Government until sold or otherwise disposed of in accordance with any conditions.

Over the remainder of the year 1899, the Department of Indian Affairs negotiated a formal surrender of the road corridor with the Nation. No money was offered for the land, and the Nation ultimately agreed to the Territorial Government building a road across the reserve with just two conditions.06 First, that a bridge be built over the Elbow river at the trail’s existing ‘Weaselhead Crossing’, and second was that if the Nation required the corridor to be fenced, they would not be asked to cover those costs. These conditions were agreed to by the Territorial Government, and on January 3, 1900 a surrender of their interest in the land was approved by the voting members of the Tsuut’ina Nation, a total of 21 citizens.07

When the surrender was agreed to by the Tsuut’ina Nation, the documentation did not contain a legal description of the land being surrendered, nor did it contain a formal survey of the route. Instead, the land being surrendered was indicated on an attached sketch showing the ‘approximate’ location of the existing trail.08

The surrender of the nation’s interests in the land was soon ratified by the Privy Council of Canada, who noted that the land was to be “…surveyed and opened up by the Government of the North West Territories as a public highway…”, though interestingly no mention of a sale was made.09 A survey would be an important step in the process, as it would serve as the legal description for the land that was surrendered for the road. In fact a proper survey of the trail had already been undertaken, but a plan showing the route had not yet been prepared by the surveyor at the time of the surrender’s ratification, and was therefore not included in the documentation.

The lack of a legal land description in the surrender documentation would cause problems for those researching and transacting with this land in the future. Anyone looking to understand what specific land was surrendered in this agreement would be forced to refer to separate survey records, as the surrender itself did not contain sufficient information to determine the extent of the surrendered lands. The ‘decoupling’ of the land description from the surrender documents would create the conditions for the original agreed-upon corridor to one day be ‘lost’ and replaced with an altered route that was not part of the original agreement.

Continue reading “Quietly Stolen Land: The Piece of Calgary Owned by the Tsuut’ina Nation”