In July of 2009, Calgary Mayor Dave Bronconnier stated “One thing is for sure. The legal access to the First Nation’s land is off of Anderson Road. And so we will have to accommodate and work with our neighbours as we always do… At the end of the day, we need to build an interchange at 37th Street SW and Glenmore (trail) and, most importantly, Calgarians just want us to get on with it.” Over the next few days, Bronconier indicated that while access to the reserve would always be maintained at Anderson Road, the access to the reserve and the Tsuu T’ina’s Grey Eagle Casino at Glenmore Trail and 37th street SW was only ‘considered temporary’. This was disputed by the Nation, and soon legal threats were issued over potential limits to reserve access.

The concept of a single, legally required access point between the City of Calgary and the Tsuu T’ina reserve has been raised in recent years by politicians and the media. So too has the suggestion that the access road to the Grey Eagle Casino is only temporary in nature. However, is this really the case? Is the City only required to provide a single connection? Is the entrance to the reserve near the casino provided as a courtesy, or does that access exist as a right of the Nation? The issue around this access point is highly charged, politically sensitive, and like most aspects of this story, comes with a long history behind it.

The oldest road in Calgary?

A route through the lands that make up the Tsuu T’ina reserve at the corner of Glenmore Trail and 37th street SW is one of the oldest roads in the Calgary region, and in fact predates the Province of Alberta and the City of Calgary. The map below from 1894 shows this entrance to the reserve as one of only a handful of significant trails in the area at the time.

In 1899 the government of the Northwest Territories sought to establish this trail as a permanent highway (later called the Priddis Trail), and in turn the Indian Commissioner sought more information about the trail in question from the local Indian Agent for the Sarcee Agency. In reply to this request, the Agent stated “The Chief informed me the trail marked in the plan was in use by the Indians before the treaty was made with them”. This was later summarized in a letter to the Secretary of the Department of Indian Affairs in July 1899 which read in part “I am informed that this road has been travelled a great many years, and is in fact one of the old trails of the district…”.

When the road was formally established in 1900, its route diverged from the original trail in the northeast section of the reserve, though the original path connecting to the city would continue to remain in regular use right up until the present day.

Military Access

A semi-permanent military camp was established on the North East corner of the Tsuu T’ina reserve in 1915 as part of the war effort, and was situated in the area where the original trail was located. The trail and entrance to this parcel of land were maintained as part of the camp’s layout, shown below in this map from 1924. When the camp was built into a more permanent barracks in the mid 1950s, the road would become the permanent entrance to the base, and would be known as Old Strathcona Road.

The land for these ‘Sarcee Barracks’ had been purchased by the Military from the Tsuu T’ina in 1952, and an entrance to the reserve continued to be maintained along this road; in the mid 1950s the Military had constructed a private bridge over the Elbow river along the original trail route, which connected the barracks with a leased artillery training area on the reserve to the south. As part of agreements made at the time, the Tsuu T’ina were given access to this private bridge and the road through the Military base was available as a route into Calgary. Despite two major interruptions in the 1980s, this arrangement would maintain access to the reserve for Nation members and continue the long tradition of the use of this trail.

The land for these ‘Sarcee Barracks’ had been purchased by the Military from the Tsuu T’ina in 1952, and an entrance to the reserve continued to be maintained along this road; in the mid 1950s the Military had constructed a private bridge over the Elbow river along the original trail route, which connected the barracks with a leased artillery training area on the reserve to the south. As part of agreements made at the time, the Tsuu T’ina were given access to this private bridge and the road through the Military base was available as a route into Calgary. Despite two major interruptions in the 1980s, this arrangement would maintain access to the reserve for Nation members and continue the long tradition of the use of this trail.

(Old Strathcona Road, based on the old trail, can be seen running diagonally at the bottom left of this image of the Harvey Barracks under construction in 1957. The road at the top right of the picture would later become Glenmore Trail)

The return and reintegration of the barracks lands into the Tsuu T’ina reserve in 1992 re-established the corner of 37th street SW and Glenmore Trail as an entrance to the reserve, and would soon set the stage for an increase in conflict over issues of access. Following the exit of the Military, the Nation had earmarked the former barracks land for commercial development, and access to these developments would play an important role for the Nation, both in terms of long-term economic plans and in the relationship with the City.

Bargaining Chips

There had been musings from representatives of the Tsuu T’ina regarding commercial developments on site of the Sarcee Barracks from as early as 1983, though it wasn’t until the land was returned and the Military had vacated the property in the mid 1990s that more definitive plans were made public.

In 2002 the Nation began the formal application for the construction of the Grey Eagle Casino on the former barracks land, and the access to the casino was raised as a potential issue from the outset. The Tsuu T’ina had approached the development with the understanding that the current access at the corner of Glenmore Trail and 37th street SW was adequate for the needs of a casino project, though not for any larger commercial development, which would require access from a ring road through the reserve. The Nation viewed the casino project and the ring road as two separate and unrelated issues.

The City of Calgary, however, took the position that any existing access could only be considered temporary pending the creation of a full access plan centred around the southwest ring road. The reason for this position lies in the possible need for an alternative route should a deal with the Nation be unsuccessful; if the ring road could not be built through the reserve, the City argued, the only alternative would be to build the ring road along Glenmore Trail and 37th street SW, which adjoins the former barracks lands on two sides. Should this occur, the existing access to the reserve at 37th street SW would have to be closed, as a high-speed limited-access freeway could not support a direct connection to a local access road like the one leading to the casino. Despite existing long before the city expanded to adjoin the reserve, Mayor Bronconier was satisfied in 2005 that the road could be unilaterally closed by the City if required.

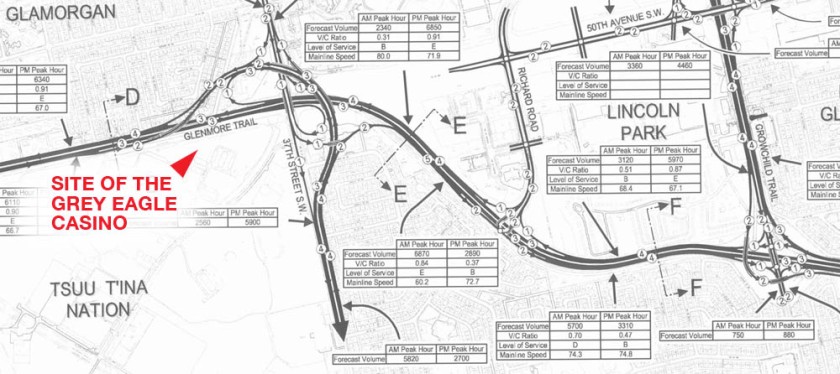

The diagram below, created as a visualization by the City of Calgary in 2002, shows the basics of a potential 37th street SW ring road/Glenmore Trail interchange with no accommodation for casino access. While this does not represent the specifics of any actual proposal, it illustrates the difficulty faced with trying to integrate Glenmore Trail, 37th street SW and a ring road with a local access road at this location.

As early as 1996, when Tsuu T’ina members first voted to endorse the plan for building a casino on the former Harvey Barracks lands, concerns about access were quick to surface. Ward 11 Alderman Barry Erskine was reported as saying that he would explore having the 37th street SW entrance to the reserve closed if a casino was built, and that the Tsuu T’ina would have to look at building a new entrance further west on Glenmore Trail or Sarcee Trail.

Though official talk of road closure was largely centred around the technicalities of maintaining commercial access at that location, some City representatives were overt in wanting to use the approval of the casino as a bargaining chip in the road negotiations. Unhappy that the Nation was pursuing a casino without first agreeing to a ring road deal, in 2005 Alderman Craig Burrows stated “we’d cut service off… (or) we can shut the access that you wouldn’t be able to get there off our road. It’s our roadway.” Burrows later stated “The worst thing that could ever happen to Calgarians is building a casino without having a ring road in place… The day they want to tie into our services and the day they think they have access to 37th Street, we are clearly telling them you could build this huge complex and it’s a risk they are taking, but we are not going to change our mind.”

In response, Tsuu T’ina representative Morten Paulsen stated “I am surprised that Alderman Burrows wants to be remembered as the first white politician to block a native reserve… The road is older than the City of Calgary. It existed for military use and it will continue to exist as an access point to the Tsuu T’ina First Nation”

When the casino approval process reached the appropriate stage to address these details, the Alberta Gaming and Liquor Commission (AGLC) dismissed concerns regarding the access from 37th street SW by referring road concerns to the City of Calgary. In a letter dated October 4, 2005, the AGLC stated “…matters pertaining to access roads fall under the jurisdiction of the City of Calgary Transportation Department. Any suggestions or comments regarding roads that you have should be directed to the City of Calgary.” Regardless of the City’s view on the fragile permanence of the access road, the casino project was ultimately approved by the AGLC, and it opened for business in 2007.

Expanding the road

The access to the Tsuu T’ina reserve at 37th street SW was not only maintained in the 2009 ring road plans, it was actually enhanced with a full interchange at Glenmore Trail and was projected to initially be increased to a four lane divided road. In the City’s view, the ring road plan was the only way to ensure the continued access to the reserve at this historic location.

Upgrades to Glenmore Trail that had originally been scheduled for the mid-2000s, which included widening of the road between Crowchild Trail and Sarcee Trail, had been put on hold while the Province negotiated with the Tsuu T’ina, and by 2005 City staff had advised the Mayor that an interchange at Glenmore Trail and 37th street (Also known as the G37 interchange) was also now required. These upgrades and the G37 interchange were included in the 2009 deal, but when this deal was rejected by the Nation, the City moved quickly to address these issues that had been delayed in anticipation of the construction of the ring road.

In July 2009, less than a week after the rejection of the 2009 ring road deal, the Calgary City Council voted to move ahead with the construction of a G37 interchange, and by September of that year, an interchange plan (below) had been approved for construction, though movement on this project would not occur without controversy.

Having initially received no formal opportunity to be consulted regarding this improvement, the Tsuu T’ina was concerned that a new interchange could impact the access to the Grey Eagle Casino. In a letter dated October 2 2009, the Nation threatened legal action if access to their reserve was compromised, stating that they “(do) not consent to any road construction on or near Tsuu T’ina Nation lands not accounting for the Tsuu T’ina Nation’s rights to enter and leave lands at any point along our borders… any interference by the City of Calgary of Tsuu T’ina Nation’s rights to enter and leave its lands at any point along Tsuu T’ina Nation boundaries constitutes a breach of our rights under Treaty No. 7.”

In reply, Mayor Bronconier noted that while he was willing to consult with the Nation, he did not believe that they had the right to dictate terms to the City, and that the City would maintain what he saw as the legal access to the reserve at Anderson Road. Regarding Tsuu T’ina concerns over alterations to city roads, Bronconier stated “We would seek their input, not their approval.”

Legal Questions

In 2008, following a year of negotiations regarding the City supplying emergency services to the Grey Eagle Casino, an editorial appeared in the Calgary Herald. Lawyer Jeff Rath, later hired by the Tsuu T’ina in an unrelated matter, blasted the City’s dealings with the Nation, and stated in part “The city does not have the legal right to prevent the Tsuu T’ina from… accessing or leaving their land at any point along their border.” He goes on to state that “If push came to shove, the Tsuu T’ina would be within their rights to construct roads in or out of the reserve, anywhere they pleased, through either municipal or provincial land, to access public roads anywhere along their border.”

Access to a reserve at any point along its boundary is not explicitly mentioned in Treaty 7, however adequate access to a reserve, especially via access points that were in use since before the Treaty was signed, may well be considered an ‘Aboriginal Right’ that would be protected by the Canadian Constitution. Aboriginal Rights are inherent rights that flow from the continued occupation of an area or the practices undertaken by First Nations that predate european contact. In the cases of Haida and Taku River in 2004, and Mikisew Cree in 2005, the Supreme Court of Canada has established that the Government has the legal obligation to consult and accommodate on issues that impact First Nation’s Treaty and Aboriginal Rights, including impacts that are the result of actions taken outside of a reserve.

This right of consultation on projects that have the potential to impact Aboriginal Rights meant that the Tsuu T’ina considered the process of planning the G37 interchange to be incompatible with established law. In the view of the Nation, any planned alterations of the access to the reserve should legally trigger a consultation process with the Tsuu T’ina separate to any other public consultations, and any impacts to the Treaty or Aboriginal Rights of the Nation would have to be identified and potentially minimized or eliminated. This duty to consult and accommodate may also mean that any ‘Plan B’ ring road route built via 37th street SW directly adjacent to the reserve could require a formal consultation process with the Tsuu T’ina even if no part of it is planned to be located on Tsuu T’ina lands.

G37 Built

As it turned out, the new (and by now significantly modified) interchange did not just maintain access to the reserve at 37th street SW via Old Strathcona Road, it actually improved traffic flow to both the casino and the community of Lakeview. The Tsuu T’ina were consulted on an ‘advisory basis’ by the City prior to construction, and the Nation raised no concerns regarding the project once it was established that the planned interchange would maintain access to the reserve. In fact, despite the posturing of some City representatives, the access to the reserve was seemingly never in danger of being cut off. On October 29 2009, the City Director of Transportation Planning Don Mulligan was quoted as saying “We have every intention and we’re committed to providing access to the casino… No question. We will be providing access one away or another . . . . The city will never block access to the casino.”

Open and Closed

Despite rhetoric to the contrary, it would seem that there is no merit to the idea that the City is only obliged to provide a single access point to the Tsuu T’ina Nation or that the access to the Nation’s casino is provided entirely as a courtesy by the City. No laws or treaties support a ‘single legal access’ concept, and in 2013 a City representative confirmed that access points between the City and the reserve are agreed upon through “bilateral discussions”. This road continues to be one of the oldest routes in Calgary, and seemingly all parties would need to be involved in any plans regarding its future.

With a new vote on a Tsuu T’ina ring road deal set for October 24, it remains to be seen if this access will be enhanced by ring road plans, or if tough decisions will be needed to accommodate the needs of all parties under alternative arrangements.

Excellent background and status on this issue.

A great summary of the devepments to date with commentary on legal issues.