This is the second in a five-part series looking at the history of the Priddis Trail. The first part, which examined the establishment of the road can be found here, and part three can be found here. I acknowledge that the resources that inform this work are largely that of non-First Nations sources, and while this is intended to be a factual look at the history of the road, it must be noted that the perspective is largely non-indigenous. I hope that further research and working with Tsuut’ina sources will reveal other equally valid perspectives on this story in the future.

—–

From Governor-Generals, Tsuut’ina Chiefs and Colonels, to Ranchers, Homesteaders and Boy Scouts, the Priddis Trail was important to a great many people for a great number of reasons. The establishment of the Tsuut’ina reserve and an early influx of Homesteaders in the late 1800s, followed not long after by the Military and a growing oil industry, meant that reliable access to a growing district was vital to the region.

(Map of the route between Calgary and Millarville through the Tsuut’ina Reserve in 1899. Source: ‘Plan Shewing survey of Old Trail and New Road from N.E. Cor. Sarcee Indian Reserve to Millarville P.O.’ A. P. Patrick. 1899. Plan 1119i, Alberta Land Titles, Southern Alberta Land Registration District )

(Map of the route between Calgary and Millarville through the Tsuut’ina Reserve in 1899. Source: ‘Plan Shewing survey of Old Trail and New Road from N.E. Cor. Sarcee Indian Reserve to Millarville P.O.’ A. P. Patrick. 1899. Plan 1119i, Alberta Land Titles, Southern Alberta Land Registration District )

BEFORE THE HIGHWAY, A TRAIL

When first formed, the route that would become the Priddis Trail was a modest dirt track used by members of the Tsuut’ina Nation and by Homesteaders living in the Priddis and Millarville districts of Alberta. Suitable for horse-and-wagon travel, the trail provided a much needed connection between these southern areas and Fort Calgary, including the burgeoning town that had begun to grow around it. In its earliest days, the land that the trail passed through had not yet been designated as the Tsuut’ina reserve1, and when the reserve was established in 1883, the use of the trail continued unabated by Tsuut’ina members and non-Indigenous settlers alike.

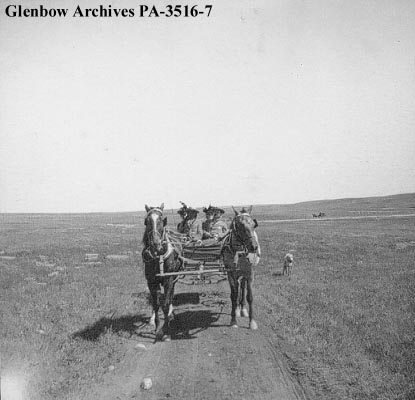

(‘Group of visitors in wagon on the way to Sarcee (Tsuu T’ina) reserve, Alberta.’ Glenbow Archives PA-3516-7. ca. 1899)

(‘Group of visitors in wagon on the way to Sarcee (Tsuu T’ina) reserve, Alberta.’ Glenbow Archives PA-3516-7. ca. 1899)

The earliest record of the Priddis Trail comes not from the path itself, but of the trail’s crossing of the Elbow river, known as the ‘Weasel Head Crossing’. In December of 1890 a newspaper article noted the Weasel Head Crossing as the site of the butchering of stolen cattle,2 making this the first mention, albeit indirectly, of both the trail and of the ‘Weaselhead’ name that this part of the Elbow river valley would later become known by.

By 1894 the first map of the route was made by the Department of the Interior3, and soon the trail was showing up regularly in newspaper accounts and official documents. In response to questions about the trail in 1899, the acting Agent of the Sarcee Agency stated: “(Chief Bull Head) informed me the trail marked in the plan was in use by the Indians before the treaty was made with them.”4, an indication of the long use of this important connection.

(A map from 1897 [with added highlights] showing the route of the Priddis Trail. Source: “Preliminary map of a portion of the District of Alberta showing Canadian irrigation surveys during 1894″. University of Alberta Libraries, Peel Map 747.)

(A map from 1897 [with added highlights] showing the route of the Priddis Trail. Source: “Preliminary map of a portion of the District of Alberta showing Canadian irrigation surveys during 1894″. University of Alberta Libraries, Peel Map 747.)

For users of the road, whether Nation members or Homesteaders, the trail enabled sustainability and economic activity by providing access to the marketplaces of Calgary. In 1893, for instance, a “comfortable dwelling house, with a good stable and corral” was built at the Weasel Head Crossing so that Tsuut’ina members had a place to stay when harvesting timber destined for sale in the City5. Former Tsuut’ina Nation Chief Sanford Big Plume also noted the use of the old trail in the Nation’s economic and cultural activities: “In the late 1800s… Once a year, Foxtail would cut small evergreens, load them on a wagon led by horses, and drive them down the Priddis Trail to Fort Calgary. There, they were sold as Christmas trees. With the proceeds of those trees, Foxtail would help fund a meal for our people, so we could also celebrate Christmas.”6

In a similar way, Homesteaders relied on the trail to bring produce and stock to market, and to access the services that the City offered.

(Postcard showing a wagon on the Priddis Trail. ‘Weaselhead district, Calgary, Alberta.’ Glenbow Archive PA-1004-18. ca. 1908.)

(Postcard showing a wagon on the Priddis Trail. ‘Weaselhead district, Calgary, Alberta.’ Glenbow Archive PA-1004-18. ca. 1908.)

Besides being functional, the trail was also noted to offer access to some of the more beautiful country in the area, and the use of the trail for pleasure would increase in popularity over the years. In the summer of 1895 the Governor-General of Canada Lord Aberdeen was touring the country, and by the summer of that year he had arrived in Calgary. On a morning in August, Lord and Lady Aberdeen were driven in the vice-regal carriage to a meeting with members of the Tsuut’ina Nation via the trail; the journey having been noted in the Calgary Daily Herald as “one of the prettiest drives in the N.W.T.”7. Forty years later, noted homesteader A.M. Stewart mirrored that sentiment in stating “…this road constitutes about the prettiest drive out of Calgary.”8 and the route was included in maps of automobile pleasure tours for the Calgary region.9

The still-nameless trail was increasingly well-used, and this usage would soon outstrip the ability of the trail to comfortably accommodate the traffic. By the end of the 1890s, muddy conditions on the primitive trail, ruts caused by wagon wheels and a lack of a bridge over the Elbow river would cause problems for travelers looking for unimpeded access. The un-maintained dirt track was proving to no longer be suitable for the use it was expected to accommodate, and Homesteaders living in the area soon lobbied to correct the situation.

FROM TRAIL TO HIGHWAY: BRIDGING THE GAP

In the spring of 1899, residents of the districts south of the Tsuut’ina reserve had been “pressing very strongly” for the land for the road to be acquired by the Territorial Government so that it could be improved “at many points where it is now in a bad state”.10 It was thought by residents that by having title to the road, the Government would invest in the route and bring the trail up to a suitable standard.

When the Government approached the Department of Indian Affairs about the possibility of acquiring the road (under threat of expropriation) the matter was referred to the Tsuut’ina Nation. Chief Bull Head agreed to allow a new road to be built along the old trail on several conditions, one of which was that a bridge was to be built over the Elbow River along the road. The Chief remarked, through the acting Agent of the reserve, that the Nation would be willing to allow the road, “but the land would be of little use… when the Elbow River is as high without a Bridge across it.”11

(‘Sarcee (Tsuu T’ina) people fording river on a trip to Guy Weadick’s ranch, Alberta.’ Glenbow Archives NA-667-740. Not Dated. While this likely does not picture the Weasel Head crossing, it illustrates the transportation conditions that were found along the Elbow river at the turn of the century.)

(‘Sarcee (Tsuu T’ina) people fording river on a trip to Guy Weadick’s ranch, Alberta.’ Glenbow Archives NA-667-740. Not Dated. While this likely does not picture the Weasel Head crossing, it illustrates the transportation conditions that were found along the Elbow river at the turn of the century.)

To this point the Weasel Head Crossing of the Elbow river consisted simply of a ‘ford’; a shallow point where horses and wagons could walk across the river. In order to provide the permanent improvements requested by the Homesteaders, a bridge was required, as demonstrated in a seemingly routine notice in the summer of 1897:

“A. Mosley, who came up from Priddis yesterday, left the hind wheels of his wagon in the Elbow River at the Weasel Head Crossing, the ford having been completely washed away.”

‘Tuesday’s News’. Calgary Daily Herald. July 8 1897.

A controversial surrender of the land by the Tsuut’ina Nation was approved in early 1900 (though title to the land was never transferred), and the Government set about satisfying the Nation’s conditions by approving a budget for the new bridge. Although title to the land was never transferred, the Government was satisfied that the land was under their ownership, and the Bridge Superintendent for the North West Territories was brought in from Regina to oversee construction of the bridge. The first steel bridge over the Elbow River, including the grading of the approaches by Tsuut’ina Nation members,12 was completed in October of 1900, about one-mile downstream from the originally agreed upon location.

(‘Bridge at Weaselhead on Elbow River, Alberta.’ Glenbow Archives NA-2569-9. ca.190-1903)

(‘Bridge at Weaselhead on Elbow River, Alberta.’ Glenbow Archives NA-2569-9. ca.190-1903)

Expectations that the Government would improve the road would be satisfied to varying degrees over the decades following the surrender. While bridges were constructed over the Elbow River and the Six Mile Coulee further south, and numerous and culverts were installed along the route, the road remained un-gravelled, and the drainage of the road proved insufficient to prevent pooling in times of heavy rainfall.

The road was built, but whether it was suitable for the job remained to be seen.

THE HIGHWAY’S FIRST 30 YEARS

The new public highway connecting Calgary with the Tsuut’ina reserve and the districts to the south was an important one, and was relied upon for access by those that lived along the route. The lack of alternatives, especially in the early days, meant that life was made more difficult when the Priddis Trail was rendered impassible by wet conditions.

The job undertaken by the Government of improving the road in the years following the surrender did not appear to impress the very people asking for such improvements, and the condition of the road was a perennial topic of discussion among ranchers and journalists. Although fine for much of the year, poor drainage, unsuitable grading, and muddy conditions were commonly heard complaints following wet-weather, and the often-poor state of the road would be problematic for users of the route for decades. In 1913 it was written:

“Residents of Priddis and Millarville are disgusted with the outrageous condition of the Priddis trail leading through the Sarcee reserve to Calgary, and intend to submit a protest to the Government unless some effort is made to put the road in passable shape. A resident of Millarville arrived in Calgary yesterday after a hard struggle to get through. He states that the stretch of road in the reservation on the brow of the hill just before the Indian’s houses are reached is nothing but a bed of muck, which is practically impassable. A little ditching, and the installation of a few culverts, he claims, would put the road in passable condition the year around.

‘Looking Backward From the Herald Files. 1913-25 Years Ago’. Calgary Daily Herald. May 30 1938.

Despite these periodic problems the road continued to see increased usage, and began to also serve purposes other than the movement of goods and local residents. The old trail had long been the mail route between Calgary and the Millarville and Priddis Post Offices, and in 1909 a short-lived telephone line was installed on poles along side the new road. A regular bus service was established over the route13 and the Military had begun using the trail to move horses, troops and artillery guns between their newly-established Sarcee Camp and leased training grounds, both located on Tsuut’ina lands. Even the Boy Scouts had begun to regularly use the Priddis Trail to get to camps that were held on the reserve. At the same time, Tsuut’ina Nation members continued to use the road to access the City and other reserves in the region, and despite growing popularity of automobiles, the number of horses on the road remained significant for decades.

The trail was well-used and relied-upon, and greater usage meant that problems persisted. In 1920 for example, the Herald reported on dissatisfaction with the route; one long-time resident of the Millarville area lamented the road’s poor condition and his inability to drive his car home from Calgary in the two months following the spring thaw that year.

(‘Places Isolated in Alberta by the Poor Roads.’ Calgary Daily Herald, April 27 1920.)

(‘Places Isolated in Alberta by the Poor Roads.’ Calgary Daily Herald, April 27 1920.)

In an effort to avoid low spots and improve the condition of the road, the Government had altered the location of the route several times, although these changes do not seem to have done enough to address the complaints of road users. Improvements by the Province, in the opinion of some, were not only ineffective, but possibly made the situation worse than if nothing had been done at all. In the same Calgary Herald article noted above, it was reported that “Mr. Millar declared that the original trails were much better than the present roads, and were passable all the year around, which could not be said of the built-up roads.”14

By the same token, a unanimously approved motion at a meeting of electors of the Municipal District of Stockland (a district that included Priddis and Millarville) in 1927 had requested that the Government move a portion of the road back to the original alignment of the old trail, citing the road’s poor condition in its present location.15 Though this request was denied, the Province’s District Engineer acknowledged the sub-standard state of the road:

“The fills on this whole road have never been built up, and in wet weather, there are many soft spots where trucks get stuck. These trucks use the road whether it is in shape to travel or not, and leave such ruts that a drag cannot fill them, and as a consequence, the road is never in first class shape.”

Letter from District Engineer to Deputy Minister of Public Works. October 27 1927. Province of Alberta Archives, GR1967.303 Box 66 41.4.45.

Despite increases in traffic and frequent complaints that the utility of the road was compromised in certain weather, the Province continued to undertake little more than routine maintenance along the route. It would take a significant event in the Province’s history for the Government to address the chronic access issues faced by residents living south of Calgary.

THE IMPACT OF THE OIL INDUSTRY

In 1914 petroleum was discovered near Turner Valley, 10km south of Millarville, which over time impacted many aspects of life in southern Alberta, including the roads. A later strike in 1924 further established both the significance of the Turner Valley oil field and the presence of the drilling industry in southern Alberta. It is this industry that had perhaps the longest-lasting impact on the Priddis Trail.

(The route between Calgary and the Turner Valley was shortest when traveled over the Priddis Trail (green) though alternatives were also found by heading first through Midnapore (blue), or through Okotoks via the McLeod Trail (red). Heavy equipment was brought to the oil fields from Okotoks via Highway 7 (orange). Source: ‘Calgary District, Alberta. Topographical Survey of Canada, Department of the Interior. 1926. University of Alberta Libraries, Peel Map 17.)

(The route between Calgary and the Turner Valley was shortest when traveled over the Priddis Trail (green) though alternatives were also found by heading first through Midnapore (blue), or through Okotoks via the McLeod Trail (red). Heavy equipment was brought to the oil fields from Okotoks via Highway 7 (orange). Source: ‘Calgary District, Alberta. Topographical Survey of Canada, Department of the Interior. 1926. University of Alberta Libraries, Peel Map 17.)

Throughout the 1920s a growing number of oil companies shipped heavy drilling equipment by rail to Okotoks, which was the closest railway depot to the oil field. From there, large trucks moved the equipment west on Highway 7 to the Turner Valley, and as a consequence the highway between Okotoks and Turner Valley became over-burdened with car, truck and heavy equipment traffic. This situation exasperated problems on a road that was already susceptible to muddy conditions and ruts.16

In the spring of 1929, wet conditions on Highway 7 became serious enough that the road became impassible to even the caterpillar-style tractors used to haul drilling equipment. Stories filled the newspapers of equipment being stockpiled in the Okotoks rail depot unable to be shipped to their destinations, and of investors being unable to drive to the oil fields, instead being forced to cancel trips or charter airplanes just to visit their operations in the Turner Valley.17

(‘Okotoks Jammed with Drilling Equipment.’ Calgary Daily Herald. May 20 1929.)

(‘Okotoks Jammed with Drilling Equipment.’ Calgary Daily Herald. May 20 1929.)

As a way to relieve pressure on the main road to the oil field, the Alberta Government began to investigate improvements to secondary roads that fed into the Turner Valley. The Priddis Trail was the most direct road between Calgary and the Turner Valley, and for years it had provided an adequate route to the oil fields. During the boom of the late 1920s, the Priddis Trail saw an increase in traffic from lighter passenger vehicles destined for Turner Valley18, and while its often-poor condition was said to limit its ability to accommodate more vehicles, the benefit of having a ‘relief’ road that could take the pressure off of other primary roads was recognized.

In February of 1930 the United Farmers of Alberta (U.F.A.) suggested to the Provincial Government that if it were to grade, drain and widen the dirt road that made up the Priddis Trail, it would help relieve other roads that served the oil fields by diverting traffic over the Tsuut’ina reserve instead. The road, it was said, has “all the traffic it can stand at the present time”19 but that improvements would allow for greater utility.

The Alberta Minister of Public Works not only agreed, but actually went further than the recommendations made by the U.F.A. The Minister was concerned that simply grading and draining the route would encourage heavy use of the road headed to Turner Valley, implying that a simple dirt road would not suffice in that capacity. He thought a bigger improvement was required, and was of the opinion that the Priddis Trail ‘should be improved to the proper standard and surfaced (graveled)’ instead.20 Within months, a special grant of $6,000 was approved for the reconstruction of the Priddis Trail through the Tsuut’ina reserve, and District Engineer F. J. Graham was directed to proceed with the work.21 It seemed that the longstanding wish of residents to have the road improved was finally becoming a reality.

HELPING THE ROAD, OR HURTING IT?

With a powerful champion, an agreeable public, a pressing need and a budget in hand, it appeared that the long-requested improvement of the Priddis Trail was imminent. This appearance was not to last long, and soon the drive to improve the road would set in motion events that would end up killing it as a public highway.

The third part of the story (found here) looks at the decline of the road, and its abandonment by the Province in favour of a new highway intended to take its place.

—–

References

1) Letter from Acting Indian Agent, Sarcee Agency, to Indian Commissioner Laird, May 16 1899. LAC. RG10, Vol. 3556, File 25 Pt. 17.

2) ‘Killing and Stealing Cattle’. Calgary Daily Herald. December 3 1890.

3) ‘Preliminary map of a portion of the District of Alberta showing Canadian irrigation surveys during 1894’. Revised 1897. University of Alberta Libraries, Peel Map 747.

4) Letter from Acting Indian Agent, Sarcee Agency, to Indian Commissioner Laird, May 16 1899. LAC. RG10, Vol. 3556, File 25 Pt. 17.

5) ‘Annual Report of the Department of Indian Affairs for the Year Ended 30th June 1893’. 1894. Government of Canada.

6) ‘Christmas reminds us of our duty to children’. Sanford Big Plume. Calgary Herald. December 10 2004.

7) ‘A Calgary Column’. Manitoba Morning Free Press. August 14 1895.

8) ‘Sarcee Reserve Road In Dangerous State’ Calgary Daily Herald. June 10 1935.

9) ‘Pioneer Work of Charting Auto Roads in Southern Alberta, Begun by Calgary Auto Club in 1911, Has Been Help to Motorists’. Calgary Daily Herald. July 17 1915.

10) Letter from Deputy Commissioner of Public Works of the Northwest Territories, to to Indian Commissioner Laird, April 24 1899. LAC. RG10, Vol. 3556, File 25 Pt. 17.

11) Letter from Acting Indian Agent, Sarcee Agency, to Indian Commissioner Laird, May 16 1899. LAC. RG10, Vol. 3556, File 25 Pt. 17.

12) Letter from Deputy Commissioner of Public Works of the Northwest Territories, to to J. McNeil, Indian Agent, Sarcee Agency. October 20 1900. LAC. RG10, Vol. 1627.

13) ‘Our Foothills.’ Millarville, Kew, Priddis and Bragg Creek Historical Society. Second Printing 1976.

14) ‘Places Isolated in Alberta by Poor Roads’. Calgary Daily Herald. April 27 1920.

15) Letter from Secretary Treasurer, Municipal District of Stockland, No.191 to A. M. Stewart, March 8 1927, and Letter from A. M. Stewart to Minister of Agriculture, Province of Alberta, March 21 1927. Alberta Provincial Archives. GR1967.303 Box 66, 41.4.45.

16) See for instance: ‘The Road Leading Into Turner Valley’. Calgary Daily Herald. May 4 1929, ‘Road to Valley is Impassible’ Calgary Daily Herald. May 4 1929, ‘The General Jumble in Okotoks These Days’. Calgary Daily Herald. May 22 1929 or ‘Bad Advertising for our Highways’. Calgary Daily Herald. June 8 1929.

17) ‘The Government and Turner Valley’. Calgary Daily Herald. June 6 1929.

18) ‘Heavy Traffic Goes Through Priddis to Turner Valley Field’. Calgary Daily Herald. May 21 1926.

19) Letter from H. Cecil Wallis, Secretary-Treasurer, United Farmers of Alberta Local 767 to Oran McPherson, Alberta Minister of Public Works. February 7 1930. Alberta Provincial Archives. GR1967.303 Box 66, 41.4.45.

20) Letter from Oran McPherson, Alberta Minister of Public Works to George Hadley, Alberta Minister of Agriculture. February 13 1930. Alberta Provincial Archives. GR1967.303 Box 66, 41.4.45.

21) Letter from H. P. Keith, Chief District Engineer to F. J. Graham, District Engineer, Alberta Department of Public Works. May 23 1930. Alberta Provincial Archives. GR1967.303 Box 66, 41.4.45.

I came upon your blog while doing research online for a novel I’m writing. I’m impressed by the thoroughness of your research into the history of the ring road.

Thank you so much. Early in the process I realized that there is a lot of poor-quality information floating around about these subjects, so I needed to be this thorough to make sure I had it right.