A growing population south of Fish Creek are demanding a road through the Tsuu T’ina reserve to be able to get to central Calgary easier. The Government has approached the Nation about routing a road through the reservation and crossing the Elbow River at the Weaselhead. If this sounds familiar, the next part probably will not: The Tsuu T’ina agree to the road, the land is surrendered at no cost, and the road is built. The year is 1900, and a road through the Weaselhead and the reserve is open to the public.

(Photo by Alison Jackson of the Priddis Trail near what is now the Weaselhead parking lot, September 29 1963. Courtesy of the Calgary Public Library, Community Heritage and Family History Digital Library.)

In 1899, the settlers and homesteaders south of the Tsuu T’ina reserve, or Sarcee reserve as it was known at the time, called upon the Government to build a road to service the area. Alberta had yet to be incorporated as a Province, and the request was made to the Government of the Northwest Territories, where Calgary was then located. Residents of the Priddis, Bragg Creek and Millarville areas had to this point relied on well established but unmaintained wagon trails to access Calgary and other ranches and towns in the region. There was pressure on the Territorial Government to formalise a road out of one of the more established trails in the area, which crossed the eastern portion of the Sarcee reserve; leading diagonally from what is now the corner of Glenmore Trail and 37th street SW to a point just north of Priddis. A trail that had been in use for many years by both members of the Nation and the early settlers of the area.

SURRENDERING THE ROAD

The pressure for better access led the Northwest Territories Government to survey the approximate location of the road, known as the Priddis Trail or Gunawaspa Tina in Tsuu T’ina, and to call upon the Department of Indian affairs to see if the Tsuu T’ina Nation would be willing to surrender the land required. On May 15 1899 the Tsuu T’ina, led by Chief Bull Head, agreed to surrender a strip of land for the road on several conditions: First, that a bridge is built across the Elbow river at ‘Weaselhead Crossing’, second; that if the road would need to be fenced, the Nation would not be called upon to pay for the fencing, and third: that the Government force settlers who grazed their cattle on the reserve be forced to pay for the right, or be removed from the land.

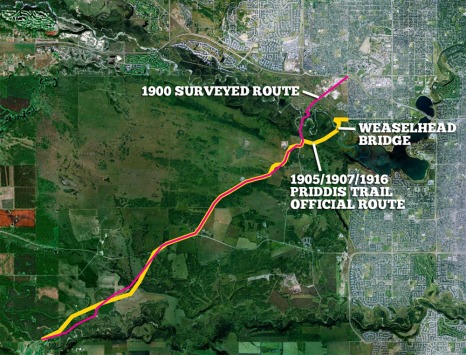

The Government of the Northwest Territories agreed to the first two conditions, but pointed out that the last condition could only be enforced by the Department of the Interior, and that they had no jurisdiction in that area. The Nation dropped the grazing condition, and eventually formalised the surrender, with the agreement being adopted by the Privy Council of Canada on February 5 1900. The Order of Council stated that the strip of land, 66 feet wide, was to be surveyed and opened up for public use as a road. (Shown above)

Surveyor A. P. Patrick completed a survey of ‘The Old Trail and New Road from N.E. cor. Sarcee Indian Reserve to Millarville P.O.’ which more fully detailed the sketch referenced in the surrender (and though dated 1900, the route appears to have been surveyed in 1899). However, by the end of 1900 the road and bridge would be under construction, but in a different location than both the surrender and this original survey indicated.

A NEW BRIDGE AND A NEW ROAD

(Glenbow Archives NA-2569-9)

In October of 1900, the Northwest Territories sent its superintendant of bridges to Calgary to oversee the construction of the new steel Weaselhead Bridge (pictured above in 1903), which was built at a cost of about $1600. The bridge, however, was located 1km further east than the original survey suggested, and the road now began at approximately 66th avenue SW, not the diagonal route from 50th avenue SW (Glenmore Trail) as was originally surveyed. It is unclear why the location chosen for the bridge and road did not accord with the surrender, nor with the survey completed only a year earlier.

The above map shows the original diagonal route in the North East corner of the reserve (pink) and the revised route, including the Weaselhead road, (yellow) that was eventually built.

This new Weaselhead road was surveyed for the first time in 1905. In the survey, the Weaselhead leg was clearly marked as a distinct road from the ‘Priddis Trail’. However, this seems to be the last time the original diagonal route was referred to as the Priddis Trail, and indeed the new Weaselhead deviation would soon be incorporated into the final layout of the Priddis Trail.

It is interesting to note that the Weaselhead road, first surveyed in 1905, will still look familiar to park users today; the modern bike path and pedestrian bridge in the Weaselhead park (shown above) follows exactly this route laid out over 100 years ago.

In 1902 and 1903 minor deviations in the route were surveyed, and in 1907 the Alberta Government re-surveyed the entire Priddis Trail, from what is now the corner of 66th avenue and 37th street SW to Priddis via the Weaselhead Bridge, apparently discarding the 1900 surveyed route once and for all. This 1907 survey, along with further revisions in 1916, would finalize the route and would constitute the full and final alignment of the road from that point forward.

TANKS, TROOPS AND TRANSPORTATION

Though surrendered and built for the benefit of the public, the 1920s saw increased use of Priddis Trail by a new group of users; the Canadian Military.

The Military first officially used Tsuu T’ina land in 1910, for summer maneuvers on the North East corner of the reserve. This corner, now known unofficially as ‘The 940‘, was separated from the rest of the reserve by the Elbow River. With the onset of World War 1, the Department of Militia and Defence began to establish a permanent barracks and training grounds on this leased corner of the reserve, called successively Sarcee Camp, Sarcee Barracks, and Harvey Barracks. In 1924 the Military also leased a large artillery range south of the Elbow River, and the road connection offered by the Priddis Trail and the Weaselhead Bridge became a vital link between the two parcels of land (see map below).

As well as being used to convey troops and equipment between the artillery range and the barracks, the Weaselhead bridge at times became a focal point for military excercises and mock ‘war games’. Even after a portion of this land was purchased by the City of Calgary for the reservoir, Military use was common. From the 1920s to the 1940s, the bridge was crossed, captured, and ‘destroyed’ (simulated, of course) many times over in war-game training involving tanks, trucks and military personel acting as both hostile and defending forces. To this day, bombs and other unexploded ordnances have been found in the Weaselhead area.

At this time, the Priddis Trail also served another important function: The 1924 lease of the artillery training area used the road to define part of its legal southern boundary.

GLENMORE RESERVOIR AND THE ACCIDENTAL PURCHASE

In the early 1930s the City of Calgary began building the Glenmore Dam in order to create a reservoir for the city, and around this time the City began buying property in the Elbow River valley that would be flooded by the dam. Part of the land needed for the reservoir was located on the eastern edge of the Tsuu T’ina reserve. This included a portion of both the barracks and artillery leases, and that we now know today as the Weaselhead park.

In 1913 the Tsuu T’ina surrendered the North East corner (or ‘The 940’) of their reserve to be sold, and in 1931 they surrendered a further 400 acres south of the Elbow River. Both of these surrenders formed the legal conditions that allowed for the City of Calgary to purchase the 593.5 acres of the Weaselhead area in 1931. Officially, this area was known as the Glenmore Reservoir lands, though it is now more commonly known as the Weaselhead Flats park, or simply ‘The Weaselhead’. (More on the North East corner of the reserve here, and more on the Weaselhead purchase here)

These surrenders, however, neglected to mention or exclude the 66-foot strip of land that contained the Priddis Trail, and when the Weaselhead was purchased by the City, the land containing the road was also sold. The ownership of this strip of land, comprising 10.23 acres and shown on the survey above, was transfered back to the Province of Alberta for continuing use as a public road. Despite being registered to the Province, the specific ownership of the road remains unclear to this day; ownership of different portions of the road may have been transfered between the Province and the City during different annexations and changes in the city limits in the 1950s, 1980s and 1990s.

The Weaselhead portion of the road, as well as the rest of the Weaselhead purchase, was also the subject of a land claim by the Tsuu T’ina. Launched by the Tsuu T’ina nation in 2001, the claim sought to confirm that the legal title of the road was never held by the City of Calgary, and that the land title ‘continues to be vested in the Crown as part of the reserve’. The claim further sought to establish that the land should have been returned to reserve status for the benefit of the Tsuu T’ina once the land was no longer required for a road. On June 6 2013 the Government of Canada ratified a settlement agreement that was reached in April, and the Priddis Trail claim, along with two other land claims, was settled for a combined $20.8 million. Further details are still outstanding.

In 1952 the Military purchased the rest of ‘The 940’ barracks land from the Tsuu T’ina adjoining the Weaselhead. However this time the surrender of the land and the purchase agreement both specifically excluded the portion of the Priddis Trail that traversed this parcel. This small, 1.2 acre portion that adjoins 37th street SW in Calgary was consequently not sold to the Military with the rest of the purchase of ‘The 940’, and today forms the northern portion of the Weaselhead parking lot.

THE STATE OF THE ROAD

Despite opening up and improving the Priddis Trail as a public thoroughfare, the route remained a dirt road for its entire public existence, and the quality of the road remained a perennial issue with travellers. Descriptions like ‘Outrageous’, ‘Impassible’ and ‘Dangerous’ had been bandied about in contemporary media for decades. Despite early efforts to maintain the road, by the early 1940s the Province stated that the portion of the road south of the Weaselhead “is not used at present” but that if required they would “rebuild the road and reconstruct bridges and culverts and again make it passable for traffic…”.

In 1952, the lease for the artillery range was altered, to require the Military to be responsible for the maintenance of the portion of the road adjoining leased land. Despite this, the state of the road continued to deteriorate, and in 1959 a key part of the northern portion of the road was eventually put beyond use. In March of that year, a mobile crane from the Atlas Construction Company of Calgary was driving over the Weaselhead bridge when a section buckled under the weight, causing the deck to collapse.

(Image CalA910724025 courtesy of The City of Calgary, Corporate Records, Archives)

No significant effort was made to repair the bridge once it was damaged, and after 59 years of service, there was no public river crossing for the Priddis Trail.

Despite the loss of the original public bridge, the Military’s access to their training grounds was not impacted, as they had built their own bridge over the Elbow River in 1950 about 1km upstream from the Priddis Trail. The Tsuu T’ina had also made arrangements with the Military so that members of the Nation were allowed to use the new bridge and road through the barracks in order to access Calgary. The private Military bridge, today used exclusively by the Tsuu T’ina, has also largely taken over the ‘Weaselhead Bridge’ moniker since the old bridge was put out of action. Most references to a Weaselhead Bridge since the 1960s tend to be in regard to this newer Military bridge (and a subsequent replacement bridge) and not the original crossing of the Priddis Trail. (More on the Military bridge, and the important role it played in Tsuu T’ina/Federal relations will be covered in a future article.)

THE OIL BOOM AND THE LOSS OF THE PRIDDIS TRAIL

Just as alternative access helped the Military and the Tsuu T’ina to remain unaffected by the loss of the bridge, so too did another alternative route help residents of the Priddis and Millarville areas remain largely unaffected by the loss of the Priddis Trail.

In 1914 oil was discovered near Turner Valley, which over time impacted many aspects of life in southern Alberta, one of which was the roads. The oil companies at the time shipped heavy equipment for drilling and exploration by rail to Okotoks, which was the closest railway station to the oil fields. From there, large trucks moved the equipment west to Black Diamond and Turner Valley. As a consequence, the main road into the area from the old Macleod Trail, as well as the old Macleod Trail itself, became over-burdened with car, truck and heavy equipment traffic. As a way to relieve the pressure on the main road, the Alberta Government built the gravelled Highway 22 from the Macleod Trail near Midnapore to Millarville and Turner Valley via the Priddis area in 1931. This road was intended to take the lighter traffic, including horses and wagons, off of the heavy equipment route. This road was well built and maintained, and quickly became a heavily used alternative to the largely neglected Priddis Trail. Interestingly, before settling on the Midnapore-Priddis-Millarville route we know today, the Priddis Trail had been earmarked as a potential route of Highway 22, to be the primary light-traffic highway from Calgary to the oil fields.

PATHWAYS AND PEDESTRIANS

In 1971 the City of Calgary approved a plan that called for the creation of walking paths through the local river valleys. The City hired 40 University of Calgary students using funding from a federal grant provided by the Opportunities for Youth program. With a further $26,000 allocated for materials from the City budget, the path building program began.

One of the first portions identified for a recreational pathway was the Elbow valley and a loop around the Glenmore Reservoir, with the portion through the Weaselhead area to follow the old Priddis Trail. However, this route had one major problem: There was no bridge in the Weaselhead, and there was no money to build a new one. The solution needed to be an inventive and thrifty one.

According to Stewart Round, head of the path building program, via an excellent article about the early days of the path building program (‘The Path Starts Here’, Chris Turner, Calgary Herald, 29 July 2005) an automobile accident was the origin of the solution for the Weaselhead bridge problem. A truck had crashed into a road sign on the Barlow Trail, leaving a support truss used for larger signs on city roadways by the side of the road. It was noted that the truss was only 10 feet short of the span required to bridge the Elbow River. With some creative earthwork to narrow the gap, the truss was installed, a deck of 2×4 wood planks was laid, and the bridge was completed without significant outlay. The signage truss is visible supporting the bridge in the photograph below.

(Glenbow Archives NA-2399-152)

For an ad-hoc development, the bridge served the City well. It lasted for 24 years, only succumbing to flooding in the spring of 1995. By October of 1995, a new bridge was built in the same location as the previous two bridges. The replacement pedestrian bridge is concrete with steel railings, and true to the spirit of the previous pedestrian bridge, it too was built using salvaged material; this time from a city overpass, which resulted in a reported 60% savings for taxpayers. The concrete bridge, officially bridge number 1606 and pictured below, is the third and most recent in this area, and still stands today.

(Photo courtesy of the Anne Elliott)

THE END OF THE ROAD…

By the 1960s the use of the road for carrying through-traffic was over. With a pedestrian path taking the place of the road in the Weaselhead, potential travellers from the south literally had no where to go. At the beginning of the 1980s, the Tsuu T’ina petitioned the Province of Alberta to have the road declared abandoned and the land returned to the Nation.

After agreeing to exclude the portion of land inside the Weaselhead park, the efforts by the Nation to repatriate the rest of the road to the South and West of the Weaselhead were successful. The Province of Alberta transfered this land back to the Federal Government in 1981 and it was set aside for reserve purposes on December 12 1985. The 10.23 acre portion inside the Weaselhead and the 1.2 acre portion that is now part of the Weaselhead parking lot were not affected by this action.

…NOT THE END OF THE STORY

Despite the road no longer existing, the Priddis Trail forms part of a larger story that still has relevance today. Beyond the recently concluded land claims on the portion of the road still held by the Province and the complicated jurisdictional issues involved, there is another contemporary reason to know the story of the Priddis Trail, one that speaks to the relationship between the Tsuu T’ina and the other levels of government in Alberta. In recent years there has been talk by some of closing the 37th street access to the Tsuu T’ina reserve near Glenmore Trail (which services the casino). While the City maintains that they are only required to maintain a single road access to the reserve, currently at Anderson Road, the Nation has spoken publicly about their right to access their land at 37th street and Glenmore Trail, in part because of a long tradition of access there. Part of the reasoning goes back to the establishment and free use of this trail by aboriginal ancestors long before Alberta was a Province, before Calgary was a City, and even before the signing of Treaty 7 and the allocation of the reserve to the Nation. Despite claims on both sides, legal access remains unclear, and would likely take a concession on one side or the other, or a legal judgement, to resolve the issue.

The next time you are in the park and are walking along the pathway, remember that you are following in the footsteps of so many pioneers, soldiers and First Nations members before you. That your journey is the culmination of many years of co-operation, conflict, necessity and negotiation.

———-

My thanks and gratitude to Karen Simonson at the Provincial Archives of Alberta, Christine Hayes at the Calgary Public Library, Ann Coffin at Alberta Transportation, Derek Green at Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada, Sandra Johnson Penney at the Canadian Military Engineers Museum and Susan Kooyman at the Glenbow Archives for their essential knowledge and assistance in researching this road.