Building the Southwest Calgary Ring Road project is a massive enterprise, and includes the construction of hundreds of kilometre-lanes of roads, 49 bridges and 14 interchanges, but the project involves more than just a freeway. One of the first projects to be undertaken in preparation for the construction of the ring road involves the relocation of an electrical transmission line; one that not only crosses the ring road corridor, but also bisects the Northeast corner of the Tsuut’ina Nation reserve.

AltaLink, the company that owns the bulk of Alberta’s electrical transmission network, is currently in the process of installing a new underground transmission line within the right-of-ways for Glenmore Trail and 37th street SW. This work is being done in advance of the decommissioning and salvage of the portion of the existing line that crosses the reserve, and the story of how the existing line ended up on reserve land, and why it is now being removed, is an interesting one that dates back almost 100 years.

The Start of the Line

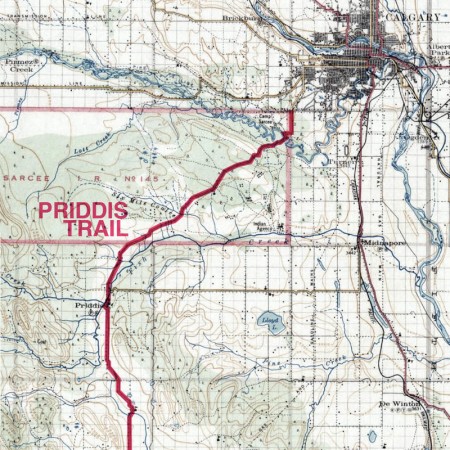

In 1924 the Calgary Power Company Ltd. planned an electric transmission line to connect their hydroelectric operations at horseshoe falls on the Bow river to south Calgary. Transmission Line No. 3 was to split off from an existing line at Jumping Pound, then head south and east for 35 kilometres to Macleod Trail at 50th avenue SW.1 Despite a few alterations over the years, this route remains largely intact and in service today.

The route for the new line was surveyed, and a corridor of between 30 and 100 feet in width was allocated to the utility, including a small section that ran through the Tsuut’ina Nation reserve (then known as the Sarcee reserve). A 3.7 km portion of the line was earmarked along the northern boundary of the Nation’s land, adjacent to what is now Glenmore Trail between about 69th street SW and 37th street SW. The 100-foot-wide corridor comprised 31.6 acres of reserve land, through an area known as Sarcee Camp or The 940.2

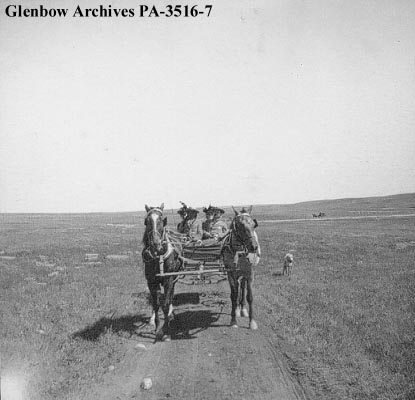

At the time of the survey, this part of the Tsuut’ina reserve was under lease to the Department of National Defence. Known as Sarcee Camp, the land had been turned into a training camp in 1915 in the midst of the First World War. When permission to cross this land was sought by the Calgary Power Company, the request was handled by the department of Indian Affairs, and no record of the involvement or approval of the members of the Tsuut’ina Nation are on file with the Federal Government.

The Federal Indian Commissioner valued a corridor agreement at $1000, which the Calgary Power Company paid in order to secure a perpetual easement for the power lines.3 On December 8 1924, the Superintendent General of Indian Affairs and representatives of the Calgary Power Company ratified the agreement, with the Department of National Defence signing off on a clause that would not hold the Military liable for “damage or injury done to the… transmission line… which may result from the use of the said Sarcee Camp for Military training…” and which would also compensate the Military for any damage caused by the operation of the line.4

With the survey in place and permissions acquired from other landowners along the entire route, the line was soon under construction. In 1926 the line was energized, and began to serve the increasing electricity needs of a growing modern city.

War and (Electrical) Power

Throughout the late 1920s and 1930s Transmission Line No. 3 operated unobtrusively side-by-side with Sarcee Camp. The camp was in regular use for peace-time training, but the outbreak of another war would change much on the Tsuut’ina reserve, including the transmission line.

In 1939 Canada became embroiled in World War 2, and military installations across Canada, including Sarcee Camp and the newer Currie Barracks to the north, were seeing increased use.

As part of the war effort, the Canadian Government earmarked Calgary as the site of a new air school. Service Flying Training School No. 3 was to be established on land directly northeast of Sarcee Camp as part of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan,5 a scheme that would see tens of thousands of airmen trained across Canada and the world during the war. The land selected for the new air school had already seen use as an airfield for a number of years as Currie Airfield, but formal runways hadn’t been constructed up to that point.

Transmission Line No. 3 crossed directly through the chosen location for the new triangular runway of the flight school, and this overlap meant that the power lines had to move. A slight relocation of the line would not suffice as the raised power lines posed a threat to taking-off and landing aircraft,6 so a more significant move was required.

In June of 1940 the Acting Deputy Minister (Air Service) of the Department of National Defence asked for permission to move the transmission line further south into the reserve, bisecting the Sarcee Camp lands. Within a few days, the Deputy Minister of the Indian Affairs Branch replied with an approval of the idea, in part because the cost of the relocation would not be charged to the Nation, and also because “…this proposed diversion will not in any way interfere with the activities of the Sarcee Indians…”.7

There is no record of any approval of the relocation by Tsuut’ina Nation members, nor of the Nation being notified of the potential move. Since the Department’s approval was granted less than a week after receiving the request, there would have been insufficient time for a formal surrender to have been granted by the Nation. As this was a case of one Federal department communicating directly with another, it appears unlikely that the request ever left Ottawa.

The same week that the Department granted permission for the transmission line move, the Tsuut’ina Nation’s Chief and Council made a related approval of their own. On June 19 1940, the Nation passed a Band Council Resolution approving the sale of gravel from the reserve to Dutton Brothers contractors, for use in constructing the new runways.8 Following a survey of the newly-altered power line corridor, the runways were under construction and nearly 5 km of the transmission line was shifted 1.6km south of its original corridor. The transmission line now diagonally crossed Sarcee Camp, and headed east through what would later become the community of Lakeview, only returning to its original route once it was clear of the airspace of the new air school.9

On the morning of October 28 1940, only 132 days after receiving permission to move the transmission lines, the flight school was officially opened. With the airspace clear and the runways built, the air school was ready to begin training new pilots and airmen. Continue reading “Electric Transmission Line Relocation”