This is the third in a five-part series looking at the history of the Priddis Trail. The first part, which examined the establishment of the road can be found here. while part two, focusing on the early years of the road is here. I acknowledge that the resources that inform this work are largely that of non-First Nations sources, and in particular this article will focus on a non-indigenous perspective on the decline of the Priddis Trail. The next article will look more at the Military’s use of the Priddis Trail, while the final part looks at the problematic legacy of this road, and will begin to address the perspective not covered in this section.

Three decades after beginning life as a Government highway, the Priddis Trail was in 1930 a well-used main road that served a growing agricultural district, a burgeoning oil industry, a First Nation and an important Military training camp.

The establishment in 1900 of the road, built along the route of an old trail that crossed the Tsuut’ina Nation reserve, was originally done in order to provide reliable access to lands located southwest of Calgary. The original trail between the city and the Priddis area was notorious for its chronically poor, often impassable condition, and it was expected that upon acquiring the corridor for the road from the Tsuut’ina Nation, the Government would create and maintain a modern and reliable road. It was this desire for better access that led homesteaders to petition the government to acquire the road in the first place, and yet three decades later, this objective remained largely unfulfilled; although a road had certainly been built, it was proving far from suitable.

(The route of the Priddis Trail (magenta) between Calgary and Millarville through the Tsuut’ina Reserve (outlined in light-pink). Source: Topographical Survey of Canada, Department of the Interior. Calgary District, Alberta. Ottawa: Department of the Interior, 1926. Peel’s Prairie Provinces Archives, University of Alberta. Map 17. Highlight added.)

(The route of the Priddis Trail (magenta) between Calgary and Millarville through the Tsuut’ina Reserve (outlined in light-pink). Source: Topographical Survey of Canada, Department of the Interior. Calgary District, Alberta. Ottawa: Department of the Interior, 1926. Peel’s Prairie Provinces Archives, University of Alberta. Map 17. Highlight added.)

The new road suffered from the same wet, periodically impassible conditions that plagued the original wagon trail. The condition of the road was exacerbated in the 1920s` by an influx of traffic brought on by an oil boom in the Turner Valley, which the Priddis Trail increasingly served. In 1930 the Province of Alberta recognized that improving the road with proper drainage and a gravelled surface would benefit both residents and industry alike, and secured funding to improve and reconstruct the road in order to make the Priddis Trail into what would soon be known as Highway 22.

HIGHWAY 22

The Province of Alberta received a formal request from the local United Farmers Association in early 1930 requesting that the Priddis Trail be upgraded to a high-standard secondary highway in order to provide alternative routes to the Turner Valley oil field, and to relieve other roads in the area that were overburdened because of an influx of heavy traffic.1 The Province soon agreed that the proposed upgrade was required, and secured a special grant of $6,000 to pay for the construction2, though in order to proceed with the upgrades, the Province first sought an agreement with the Municipal District of Stockland to cost-share the project. The Priddis Trail did not just cross the Tsuut’ina reserve, but it also traversed the M.D. of Stockland to the south, and while the Province was responsible for construction and maintenance of the road through the reserve, local Municipal Districts were responsible for half of the costs of local highways within their boundaries.

The Province’s request to cost-share this portion of the road resulted in the matter being discussed at a Stockland Council meeting on June 16 19303. In the meeting, the Stockland Council unanimously agreed to their participate in the project, though not using their own money. A special road construction fund had been established by the Province and funded by the oil industry to build and repair roads in the Turner Valley area that had been damaged by industry activity, and it was this fund that was specifically called upon to pay the M.D.’s portion of the construction of Highway 22. And although agreement was reached in improving the area’s primary highway, the M.D.’s vision of the project differed from what the Province had initially proposed.

(Map of change in location of secondary highway to Turner Valley between Midnapore and Millarville (green). Source: Google Maps and Topographical Survey of Canada, Department of the Interior. Calgary District, Alberta. Ottawa: Department of the Interior, 1926. Peel’s Prairie Provinces Archives, University of Alberta. Map 17. Highlights added.)

In agreeing to the project, the Council’s motion described the route of the road in a way that veered significantly from the existing Priddis Trail. Rather than heading north from the Turner Valley and then across the Tsuut’ina Nation reserve towards Calgary, the newly proposed route avoided the reserve entirely. The deviation would head due east once the highway neared Priddis, and then connect to the Macleod Trail just south of Midnapore, a route we now know as Highway 22x.

Although no reason was given for this alteration at the time, the Calgary Daily Herald later suggested that the route was changed in order to avoid the ‘long unoccupied stretch of country on the (Tsuut’ina) Reserve’ so that it could instead serve the ‘fine stretch of agricultural districts’ southwest of Midnapore.4 A later assessment of the old trail by local District Engineer F. J. Graham stated that it was crooked and situated in a poor location, and that it was difficult to maintain as there were few residents living along its route in the reserve that would voluntarily ‘drag’ the road to eliminate ruts.5 It is also interesting to note that the new alignment for the highway would normally have cost the local Municipal District far more that the original route, as it continued within the boundaries of the M.D. for several miles longer than the Priddis Trail. The decision to re-route the highway and serve more of this district was undoubtedly helped by the existence of an oil industry-funded reserve that paid the M.D.’s share of the construction costs.

Beyond these factors, there was another emergent issue that would impact the conversation over the fate of the Priddis Trail: the construction of the Glenmore dam and the flooding of the Elbow river valley for a reservoir.

THE GLENMORE RESERVOIR

Following the approval of the highway project by the Municipal District of Stockland in 1930, the Province’s local District Engineer immediately noticed the proposed alteration of the highway’s alignment, and asked the Government if this change would be acceptable. Chief District Engineer H. P. Keith was instructed to go over the route and ‘bring in a recommendation as to whether or not location of secondary highway should be changed…’6 giving the question particular consideration in light of the impending creation of a reservoir in the Elbow valley.

(Location of the Priddis Trail (magenta) crossing the land initially surveyed for Calgary’s reservoir site (blue) on the Elbow river. Source: ‘Plan showing the outlines of the area affected by the projected municipal water supply for the city of Calgary on the Elbow river’. Library and Archives Canada. NAC RG10 Vol. 6613 File 6120-1. 1930/01/24. Highlights added.)

In 1929 the City of Calgary had approved the construction of the Glenmore dam on the Elbow river in order to flood the Elbow valley and create a new reservoir for the city. The Priddis Trail crossed the Elbow river by way of the Weasel Head Bridge located at the west end of the proposed Glenmore reservoir, but the extent of the flooding at the west-end of the reservoir, the Weaselhead area, was apparently not well understood by all involved.

In seeking an opinion on the change of the road’s route to Midnapore, Deputy Minister for Public Works J.D. Robertson asked that Chief District Engineer Keith consider the possibility of having to move the location of the Weasel Head Bridge and the Priddis Trail anyway if the reservoir impacted the route. The decision to move the highway was solidified by the looming creation of the Glenmore reservoir, and Keith later stated “…I understand that it is likely that the trail would be entirely cut off by (the reservoir).”7

‘Where City’s Water Supply Will Come From’ Calgary Daily Herald. July 26 1930.

This uncertainty over the impact of the Glenmore dam and reservoir on the Weaselhead area was not limited to Provincial representatives, as representatives of the City and the Tsuut’ina Nation were also apparently not fully informed about the extent of the flooding for the reservoir. In 1931 the Edmonton Journal reported on negotiations for the purchase of the Weaselhead area from the Nation, ‘500 acres of land to be flooded in construction of the Glenmore reservoir’8, and noted that the Tsuut’ina negotiators were dismayed over the loss of the name ‘Weasel Head’. There was concern that once the dam was completed, the entire Weaselhead area would lie at the bottom of the reservoir, and the long-standing name for the area would be lost once the land was no longer accessible. It was reported that following the conclusion of negotiations, and after some consideration by Tsuut’ina Nation members, the name of ‘Weasel Head’ was honorarily bestowed on the City’s negotiator, solicitor L. W. Brockington, as a way to ensure that the name would live on.9

‘Indians, City Reach Agreement’ Calgary Daily Herald. May 5 1931.

While we now know that the area would continue to be known as the Weaselhead and the location of the Weasel Head bridge would not be impacted by the presence of the reservoir, in 1930 these considerations were very real.

ALTERING THE ROAD

In 1931 the Province of Alberta, with the co-operation of the Municipal District of Stockland, began to grade and construct the road that would come to be known as Highway 22. The Province expended an astonishing $113,000 over two years10 to construct the road along the newly-agreed route to the Macleod trail near Midnapore, the road now completely bypassing the Tsuut’ina Nation reserve.

‘Gravel crushing outfit south of Midnapore, Alberta.’ 1937. Glenbow Archives NA-1218-1. Preparing gravel for construction of nearby Macleod Trail.

In the years following its construction, new highway was lauded in the local press as ‘Splendid’11; a well-built and reliable road to serve district residents and local industry12. Three decades after settlers first requested that the Government acquire a route through the Tsuut’ina Nation reserve in order to improve access, homesteaders were finally well-served by a suitable road. Of course, homesteaders were not the only users of the old road, and Highway 22 did not serve one important user group as well as the old trail did: members of the Tsuut’ina Nation itself.

Chief Engineer H. P. Keith stated in May of 1932 that the new highway was intended to ‘take care of practically all of the traffic formerly using the trail across the Indian Reserve’13. With this in mind, and given his understanding that the Glenmore reservoir would likely flood the trail, he instructed the local engineer to discontinue maintenance of the old Priddis Trail. This decision to discontinue use of the old road would mark the beginning of the end of the Priddis Trail as a public highway.

‘VIRTUAL ABANDONMENT’

In the first half of the 1930s, in the years following the opening of Highway 22, the lack of maintenance on the Priddis Trail meant that the old road was allowed to degrade to a condition previously unseen, even for this chronically poor route. The Province had initially left the road open to the public, even after discontinuing maintenance, but the potential danger of the road soon became apparent. The Government had removed some of the culverts along the route, exacerbating the muddy conditions and hastening the damage that standing water would do to the road.

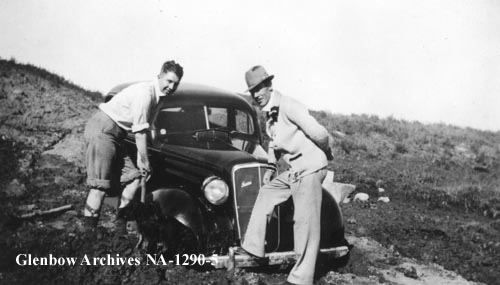

‘Automobile stuck in mud near Fish Creek area, Alberta.’ ‘Taking second troop scouts to camp on Sarcee (Tsuu T’ina) Reserve. May 24 1936. Glenbow Archives NA-1290-5.

In June of 1935 Priddis resident A. M. Stewart wrote to the Calgary Daily Herald to decry the condition of the trail, apparently unaware of the Province’s decision to unofficially abandon the road. In noting the road’s ‘disgraceful condition’, Stewart stated that “…in its present state it is a positive danger to any motorist who attempts to cross it.”14 He went on to note that although the road was being neglected, he recently witnessed the Weasel Head Bridge being repainted, and questioned the wisdom of maintaining the bridge but not the road that it served. (Unbeknownst to Stewart, the Province had a reason for this maintenance imbalance, which will be explored in part 4 of this series.)

The following year an ‘enthusiastic’ meeting took place in Priddis of local residents wanting to discuss the state of the Priddis Trail. The Calgary Daily Herald summed up the concerns of residents by reporting:

“With the taking out of the culverts on the Priddis-Sarcee trail, and the virtual abandonment of the road by the government, a great hardship is wrought on a large section of farmers living west and south of Priddis. Many of them have no cars, and besides placing local settlers from ten to eighteen miles farther away from Calgary if (Highway 22) is followed, there is grave menace to horse-drawn vehicles travelling this road on account of heavy motor traffic from the oilfields.”15

Only 69 automobiles were owned by First Nations and their members in the entire of Alberta in 193516, and few are likely to have been available at Tsuut’ina, so while ranchers and settlers were vocal about the hardships caused by loss of the Priddis Trail, Nation members were seemingly hit disproportionately hard by the abandonment of the road.

‘Priddis, Alberta store and post office.’ ca. 1932. Glenbow Archives NA-317-2

A delegation including Stewart was appointed to take the concerns of residents to the Government to advocate for the road to be returned to a passable state, and a petition was sent to William Aberhart, Premier of Alberta and MLA for the Priddis area. At about the same time, the Province’s neglect of the road led to the collapse of a bridge across the Six-Mile Coulee17, and it was this collapse that finally led the Government to confront the problems faced by travellers who still used on the old trail, though perhaps not in the way local residents would have preferred.

Around 1936 the Department of Public Works erected ‘Road Closed’ signs at each end of the portion of the road that crossed the Tsuut’ina reserve; as far as the Government was concerned the road was closed to the general public. Despite the signage, no formal road closure was enacted, and even the local District Engineer remarked that ‘…the status of the road is obscure at present’.18

THE ROAD AHEAD

With the opening of the new Highway 22, traffic on the Priddis Trail became increasingly light, and this reduction in demand meant that the Province was comfortable in declaring the old road closed. If that road had only been used by ranchers and members of the Tsuut’ina Nation, it’s likely that the 1930s would have marked the end of the road’s brief but eventful life. However, the Priddis Trail had another important primary user, so the story of the old trail would not end there; the Military had been using the road for at least a decade by the time the Province was ready to declare it closed, and with a world war on the horizon, the Priddis Trail still had life in it yet.

The fourth part of the story will look at the Military’s use of the Priddis Trail and the priority that the it would receive from the Province, often to the detriment of the Tsuut’ina Nation. The final part will look at the legacy of the issues surrounding the Priddis Trail, and the lasting impacts still being addressed today.

References

1) Letter from H. Cecil Wallis, Secretary-Treasurer, United Farmers of Alberta Local 767 to Oran McPherson, Alberta Minister of Public Works. February 7 1930. Alberta Provincial Archives. GR1967.303 Box 66, 41.4.45.

2) Letter from H. P. Keith, Chief District Engineer to F. J. Graham, District Engineer, Alberta Department of Public Works. May 23 1930. Alberta Provincial Archives. GR1967.303 Box 66, 41.4.45.

3) Letter from W. H. King, Secretary, Municipal District of Stockland, No. 191, to F. J. Graham, District Engineer, Alberta Department of Public Works. June 16 1930. Alberta Provincial Archives. GR1967.303 Box 66, 41.4.44.

4) ‘Highway 22 Has Stood Up Under Weight of Traffic Not Expected When Built’. Calgary Daily Herald. January 27 1938.

5) Memorandum from F. J. Graham, District Engineer, Alberta Department of Public Works to A. Frame Esq., Superintendent of Maintenance, Alberta Department of Public Works, June 25 1947. Alberta Provincial Archives. GR1967.303 Box 66, 41.4.45.

6) Letter from J. D. Robertson, Deputy Minister of Public Works, to H. P. Keith, Chief District Engineer, Alberta Department of Public Works. June 26 1930. Alberta Provincial Archives. GR1967.303 Box 66, 41.4.44.

7) Letter from H. P. Keith, Chief District Engineer to F. J. Graham, District Engineer, Alberta Department of Public Works. May 11 1932. Alberta Provincial Archives. GR1967.303 Box 66, 41.4.45.

8) ‘Calgary City Solicitor Now Known By Sarcees as ‘Chief Weasel Head’’. Edmonton Journal. May 5 1931.

9) ibid.

10) Annual Report of the Department of Public Works of the Province of Alberta 1930-31, Page 14, and Annual Report of the Department of Public Works of the Province of Alberta 1931-32, Page 14. Peel’s Prairie Provinces Archive, University of Alberta. Items 9536.25 and 9536.26.

11) ‘What’s In A Name?’. Calgary Daily Herald. February 4 1937.

12) ‘Highway 22 Has Stood Up Under Weight of Traffic Not Expected When Built’. Calgary Daily Herald. January 27 1938.

13) Letter from H. P. Keith, Chief District Engineer to F. J. Graham, District Engineer, Alberta Department of Public Works. May 11 1932. Alberta Provincial Archives. GR1967.303 Box 66, 41.4.45.

14) ‘Sarcee Reserve Road in Dangerous State’. Calgary Daily Herald. June 10 1935.

15) ‘Ask Repair of Old Mail Route Sarcee Reserve’. Calgary Daily Herald. February 5 1936.

16) Dominion Of Canada Annual Report of the Department of Indian Affairs for the Year Ended March 31 1935. Government of Canada. Library and Archives Canada. Page 33.

17) Memorandum from F. J. Graham, District Engineer, Alberta Department of Public Works to A. Frame Esq., Superintendent of Maintenance, Alberta Department of Public Works, June 25 1947. Alberta Provincial Archives. GR1967.303 Box 66, 41.4.45.

18) Letter from F. J. Graham, District Engineer, Alberta Department of Public Works to E. D. Robertson, Superintendent of Maintenance, Alberta Department of Public Works, April 4 1938. Alberta Provincial Archives. GR1967.303 Box 66, 41.4.45.

Always a pleasure to read your blog.

Another informative and well-written post! Keep up the great work – I would still like to connect for a coffee at some point.

Ken Gummo

Sent from my iPhone

>

Very interesting. I look forward to reading Part 4 of The Rise and Fall of the Priddis Trail. Will it be forthcoming? I don’t see it listed since Part 3 was posted in 2016. I have always wondered about how the Glenmore Reservoir was sited, and this post filled in a lot of detail. Finally, do you know of any terrain maps of the Calgary region made before the city expanded. I would like to see how the different river valleys and plateau blocks looked before settlement. They seem difficult to find, at least online. Thanks!

Fascinating read. Thanks for posting. So many hours as a child in Weaselhead, on that strange bridge/road… too wide to be a trail, not connected to anything like a road. And now on Google Maps, any number of those ghostly old trails are still there to be seen.